Silence Is Consent: White Feminism’s Selective Solidarity With Iran but Not Palestine

by Zara Choudhary in Culture & Lifestyle on 14th December, 2023

Liberal feminism, or ‘White’ feminism as it has come to be known, seems to employ two instruments in its activism: the use of the voice, and the employment of silence. Silence here is not the passive absence of words, but an active choice with a clear objective.

When a young Kurdish woman, Jina Amini, was killed at the hands of Iran’s “morality police” for wearing her hijab ‘improperly’, there was, justly, international outrage. Protests erupted around the country, as Iranians took to the streets to demand justice for Amini, as well as increased rights for women and the dissolution of the mandatory hijab law. Some female protestors publicly removed and burned their hijabs, while others cut their hair as an act of defiance.

In Europe and the US, women’s groups, human rights advocates and female celebrities voiced their support for Iranian protesters, with some even cutting their hair in solidarity. The consensus amongst Western feminists was clear: Iranian women must be supported in their struggle.

A year later, as a human catastrophe unfolds in Gaza, disproportionately affecting women and newborns according to the WHO, those same feminists who used their voices and their platforms to (rightly) advocate for their Iranian sisters, are now employing a different approach: silence.

As Gaza’s besieged women have bombs dropped upon their heads, those who claim to advocate for women’s rights, are silent.

As Gaza’s grieving mothers wrap their dead children in burial shrouds, those who claim to work for the eradication of violence against women and children, are silent.

As Gaza’s pregnant women are forced to undergo caesareans without anaesthetic, those who claim to campaign for women’s access to health services, are silent.

As Gaza’s schoolgirls lie lifeless beneath the rubble of their bombed schools, those who claim to support the right to education for all females, are silent.

As Gaza’s women and girls face a genocide that is being live-streamed for the world to see, those who claim to believe in equality for all, are silent.

But in the absence of words, their silence speaks volumes.

White Feminism

The deliberate silence of these self-proclaimed champions of women’s rights is both wilful and entirely predictable. Their failure to advocate for Palestinian women reflects a pattern rooted in the foundations of White Western Feminism. This will be explained further but first, we must define terms.

The term ‘feminism’ is often misused by Muslims who attempt to criticise ideals and objectives that they deem incompatible with their understanding of religion. Feminism, however, does not denote a single ideology but rather acts as an umbrella term for various socio-political movements and ideologies that attempt to address a plethora of issues faced by women. They often have differing aims and historical frameworks.

In recent years, liberal or mainstream Western feminism, often labelled as ‘White’ feminism, has come under scrutiny. It is used to describe the thinking of individuals who tend to universalise the objectives, experiences and beliefs of white women, often neglecting the perspectives of racialised minorities in the West and ‘other’ women around the world. It is crucial to note that not all feminists who are white subscribe to this mindset, and some of those who do, are not white women (1).

By centering the experience of white (usually middle-class) women, White feminism fails to consider the role of other social identities in gender-based discrimination. While White feminism tends to be exclusionary in practice, the rise of intersectional feminism (2) in the last decade has provided an analytical framework that enables a deeper understanding of the intersections of gender, race, religion and other identities.

Though the term was coined by professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, Black feminists as early as Sojourner Truth in the 1850’s, were already articulating the unique social challenges they faced as Black women. Since Crenshaw, numerous strands of intersectionality have emerged, but on the whole, feminists who are intersectional in their activism, tend to view the struggle of Palestinians as that of a marginalised community resisting an oppressive power. It is clear that Black and Indigenous feminists, as well as those belonging to marginalised communities, have generally been vocal in their support for the people of Gaza.

The focus of this article is White Western feminism. I have written previously about the orientalist roots of this type of feminism, beginning with Mary Wollstonecraft, that used the ‘Eastern’ woman as a foil against which the enlightened, civilised Western woman could be defined. The strategy was employed as a rhetorical device that allowed feminists to argue for their emancipation in the West. They built arguments around the passivity and servility of an imagined Eastern womanhood, not through any concern for the latter, but rather to convince their Western male counterparts that by denying Western women emancipation, they were behaving like Eastern men. Notions of the inferiority and barbarity of the East were so entrenched in Western society, that the implied meaning was clear to all (3).

Not only did Western feminists differentiate their womanhood from an Eastern one (based on Orientalist assumptions rather than observed reality), they turned the Eastern woman into an object of humanitarian concern, allowing themselves the opportunity to partake in imperial endeavours.

Imperial Feminism

In a British context, proponents of women’s rights considered it their duty to assist British men in the colonies. Figures such as Mary Carpenter and Bayle Bernard encouraged their fellow Englishwomen to take on professional roles in the colonies to ‘aid’ their ‘sisters’ – roles which were unattainable in Britain itself due to gendered restrictions. They were thereby able to prove “to all those who stayed at home that the empire was not simply the project of the British man but that it belonged to women as well.” (4)

Feminist literature such as The Englishwoman’s Review, was instrumental in spreading this message (5), alongside the view that the empire was a force for good in the world. This was often articulated in Christian missionary language, aiming to bring the light of faith to the “heathen populations of the East.”

In British-ruled India, feminists focused on the education of the ‘downtrodden’, ‘servile-minded’ Indian woman (also a feminist construct), but their strategies differed in the colonies of Africa and the Middle East.

Egypt provides a particularly interesting example. In the Western discourse on Islam, already replete with references to the subjugation of women and their segregation from society, feminist concerns in Muslim colonies, including Egypt, were centred around the perceived oppression of Muslim women both by Muslim men and the Islamic religion. Ironically, this narrative was also used as the moral justification for Britain’s imperialist intervention in the region. Men appropriated feminist language for imperial aims, while the very same men denied feminist demands back home.

As Leila Ahmad has shown, Lord Cromer, British consul general in Egypt from 1883–1907, used feminist rhetoric to further the ‘civilising’ aims of the colonial mission. He did so while actively pursuing policies that were detrimental for Egyptian women, restricting their education. He believed that Islam’s ‘subjugation of women’ was a prime factor in the inferiority of Islamic civilisation, and urged Egyptians to give up the practices of segregation and the veil. But as Ahmad notes, “This champion of the unveiling of Muslim women” was, in England, a founding member of the Men’s League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage (6).

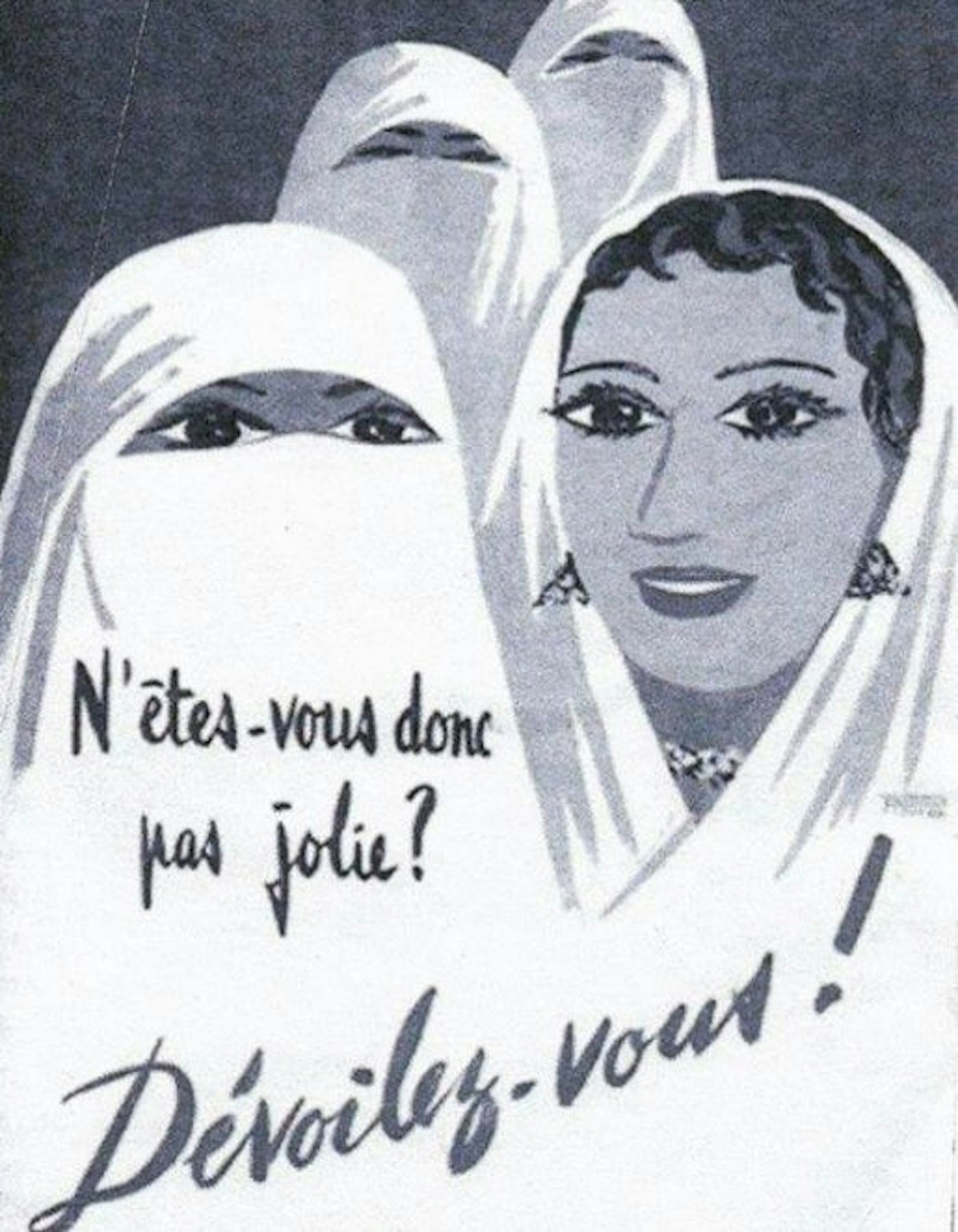

In the French colonies of North Africa, a major purported aim of the colonial project was the liberation of women, and once again, the act of unveiling was a central and visual sign of ‘progress’. In the Algerian context, the veil became a symbol of Algerian resistance to colonisation (7). Frantz Fanon, psychiatrist and political philosopher, writes that the French authorities, “committed to destroying the people’s originality, and under instructions to bring about the disintegration…of forms of existence likely to evoke a national reality…were to concentrate their efforts on the wearing of the veil, which was looked upon at this juncture as a symbol of the status of the Algerian woman.” (8)

During the Algerian War of Independence in the 1950s, French propaganda sought to present an image of French-Algerian unity to the world. The army organised mass gatherings in front of international media, showcasing ‘reconciliation’ between the Muslim population and European settlers. As part of these gatherings, unveiling ceremonies were conducted to demonstrate the ‘success’ of the French colonial enterprise in ‘liberating’ Muslim women from the constraints of their religion and culture. In one such ceremony, a group of Algerian women burned their veils, while in another, European women unveiled their ‘sisters’ (9).

According to the sociologist Marnia Lezreg, these ceremonies did lasting harm to Algerian women, “It brought into the limelight the politicisation of women’s bodies and their symbolic appropriation by colonial authorities. It brought home to Algerian women their vulnerability…Their sexed body was suddenly laid bare before a crowd of vociferous colonists who, in an orgy of chants and cries of “Long Live French Algeria,” claimed victory for all Algerian women.” (10)

This act of unveiling was also accompanied by an element of erotic obsession on the part of male French colonists. I’ve written previously about French colonial photography and the erotic studio images capturing Algerian women in various stages of undress. Given the politicisation of the veil and its connection to anti-colonial resistance, unveiling was seen, in Fanon’s words, as “a negative expression of the fact that Algeria was beginning to deny herself and was accepting the rape of the colonizer.” (11)

As Lazreg has detailed, the veil also made colonial French women uncomfortable, serving as a constant, visual reminder of their powerlessness in erasing the existence of a different way of being a woman (12). One could argue, given recent events in France concerning the dress of Muslim women, that this still continues to be the case.

Post-Colonial ‘Feminist’ Wars

In the post-colonial era, public discourse in the West has changed; overtly racist and missionary language is no longer considered acceptable, both in a political-imperial context and a feminist one. The rhetoric of liberal feminism is no longer couched in Christian ideals, but rather uses the language of secular humanism. The union between Western imperialism and white feminism, however, is still fully intact.

Justifications for the US-led war in Afghanistan were framed in considerable part around the liberation of Afghan women. For this reason, Rafia Zakaria, author of Against White Feminism, refers to the War on Terror as ‘feminist’, since the rights of women were positioned as a purported goal of military intervention. She states, “American women were liberated, and now they, along with male service members, would go to Afghanistan to root out the misogynist regime of the Taliban. America was thus not a cruel superpower bombing a much smaller nation, but a force for good, helping to bring gender equality to a war-torn country.” (13)

In the lead up to the invasion, as noted by the Palestinian-American anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod, mainstream media discourse did not focus on the history of repressive regimes in the region and the role of the United States in this history. Instead, it was centred around religion and culture, particularly the treatment of women. Her remarks are worth reading.

“Instead of political and historical explanations, experts were being asked to give religious or cultural ones. Instead of questions that might lead to the examination of internal political struggles among groups in Afghanistan and other nation-states, we were offered ones that worked to artificially divide the world into separate spheres—re-creating an imaginative geography of the West versus East, us versus Muslims, cultures in which first ladies give speeches versus others in which women shuffle around silently in burqas.” (14)

As we previously observed, this was the same strategy employed by Western colonialists, including an intense focus on the veil. The burka became a symbol of the barbarity and misogyny of the Taliban, and a cultural ‘other’. It helped cement the binary of ‘us’ and ‘them’ which was crucial in the colonial period. In a feminist context, the burka became a visual representation of a ‘pitiable’ figure who needed saving by her Western ‘sisters’.

In 2002, a coalition of Western women’s groups wrote an open letter to George Bush pleading for military intervention in Afghanistan for the sake of Afghan women (15). The Feminist Majority, a US-based feminist organisation, ran a campaign against the Taliban’s treatment of women, gathering support from Hollywood celebrities and feminists alike. Feminist journals and women’s magazines also directed their readers’ attention to the plight of Afghan women.

Charles Hirschkind and Saba Mahmood point out that there was a failure among commentators to connect the predicament of Afghan women with the role the US had played in creating those miserable conditions.

“This silence, a concomitant of the recharged enthusiasm for the US military both within academia and among the American public more generally, also characterised much of the response both to reports of mounting civilian casualties resulting from the bombing campaign, and to the widespread famine that the campaign threatened to aggravate.” (16)

They note that the Feminist Majority website continued to concentrate on the ills of the Taliban even as 2.2 million Afghans faced an increased risk of starvation due to the severe restrictions on the delivery of food aid caused by US bombing.

The point here is not to deny that Afghan women were living in brutal conditions before the war, but to highlight that the brutality they suffered at the hands of their American ‘saviours’ (and indeed their role in helping to create the conditions in the first place) is simply ignored by white feminists. Their intervention focused on ‘saving’ the Afghan woman through her education and freedom to remove the burka, even if that meant bombing her family out of existence.

As Abu-Lughod asks, “How many who felt good about saving Afghan women from the Taliban are also asking for a radical redistribution of wealth or sacrificing their own consumption radically so that Afghan, African or other women can have some chance of freeing themselves from the structural violence of global inequality and from the ravages of war?” (17)

Silence as Consent

At the time of writing, the death toll following the Israeli bombardment of Gaza has reached 18,000, with many more bodies believed to be trapped beneath the rubble. According to the UNRWA, more than two-thirds of those killed are women and children. There are an estimated 50,000 pregnant women in Gaza with more than 180 giving birth every day. 15% are likely to experience pregnancy or birth-related complications and need additional medical care. Some are having to give birth amid rubble and on the streets due to overwhelmed health services and bombed hospitals. These are just a few of the many devastating consequences of the Israeli campaign to displace the population of Gaza.

The extent of the carnage prompts the question: Why are white feminists silent? Are the women of Gaza not as deserving of feminist support and advocacy as Iranian or Afghan women?

Chakravorty Spivak’s famous line is relevant here, liberal feminists support “white men saving brown women from brown men.”(18) Their advocacy depends upon who the perpetrators are, and which worldview they are promoting – irrespective of the means by which they attempt to achieve it, or the devastation they leave in their wake. Committed to Western imperialism, white feminist advocacy only extends as far as imperial aims will allow it to. The settler-state of Israel, is, from its very conception, a Western imperial project. This is why the plight of Afghan women and Iranian women (the ‘victims’ of brown men) elicited such emotive, vocal support, and why Palestinian women have, despite decades of documented suffering under Israeli occupation, been met largely with silence.

Their silence is an active choice, it is consent.

White feminists cannot feign ignorance or a lack of courage. Capable, intelligent women, who have frequently defied societal norms on controversial women-related issues, even at the cost of their personal careers and reputations, typically do not stay silent in the face of genocide, unless they implicitly support the underlying imperial aims being carried out.

Their silence on this issue reveals more than they would ever be willing to admit. Their feminist ideals are tailored towards a very specific worldview that aligns with Western imperialism leaving no room for other visions of womanhood. Basic morality at its most fundamental level is of no consequence if it interferes with or endangers this worldview.

This is how the silence of those who have made careers from feminist advocacy must be interpreted. I have chosen not to name individuals, but one has to only take a look at the public discourse of those who in recent years have claimed to defend women’s rights from trans-ideology, or those who have become celebrity adjacent human rights activists and lawyers, or even mainstream liberal women’s organisations and charities in the West that purport to champion diversity. I can almost guarantee you one thing, they have found the time to advocate for Iranian women’s rights to remove the veil.

White feminism has an unspoken principle: the ends justify the means. Violent intervention is supported, even encouraged, if white feminist ideals are being ‘instilled’. Because for the white feminist, there is but one vision of womanhood, and it does not don a veil.

Silence is consent. To the Western human rights activists, women’s groups, celebrity feminists evading moral and ethical responsibility: In the absence of your words, your silence is speaking for you.

Bibliography

- For a more detailed analysis of White Feminism, see Rafia Zakaria’s Against White Feminism (2021).

- ‘Intersectionality’ is a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, Columbia scholar and Professor of Law at the University of California, Los Angeles. See her foundational 1989 article “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics”.

- Read “Subordinate Beings: The Orientalist Roots of Western Feminism” by Zara Choudhary for a detailed historical analysis.

- Zakaria, 2021, p.20.

- See Antoinette M. Burton, Burdens of History: British Feminists, Indian Women, and Imperial Culture, 1865-1915 (1994).

- Leila Ahmad, Women and Gender in Islam (1992), p.153.

- See “Unveiling the Algerienne: French Colonial Photography” by Zara Choudhary for more.

- Franz Fanon, “Algeria Unveiled”, Decolonisation: Perspectives From Now And Then. Ed. Presenjit Duara.

- Neil MacMaster, Burning the Veil: The Algerian war and the ’emancipation’ of Muslim women, 1954-62. (2012).

- Marnia Lazreg, “The Eloquence of Silence” (1994), p.135-6.

- Franz Fanon, “Algeria Unveiled”, Decolonisation: Perspectives From Now And Then. Ed. Presenjit Duara.

- Lazreg 1994, p.136.

- Zakaria, 2021, p.69.

- Lila Abu-Lughod, Do Muslim Women Need Saving? (2013), p.31-2.

- Zakaria, 2021, p71.

- Hirschkind, Charles, and Saba Mahmood. “Feminism, the Taliban, and Politics of Counter-Insurgency.” Anthropological Quarterly, vol. 75, no. 2, 2002

- Abu-Lughod, 2013, p.42.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak? Die Philosophin 14 (27):42-58.

Zara Choudhary

Zara is the founder and editor of Sacred Footsteps, an online publication dedicated to spiritual & alternative travel, history & culture from a Muslim perspective. Alongside our articles and guides, our podcast aims to highlight aspects of history and culture that are often overlooked, as well as trends within travel and the so-called ‘halal travel’ industry that aims to cater for Muslim travellers. We now offer uniquely packaged tours, that have a particular focus on encouraging sustainable, ethical and responsible travel practices. You can find Zara on Twitter @ZaraChoudharyX and IG: @zara_choudhary/