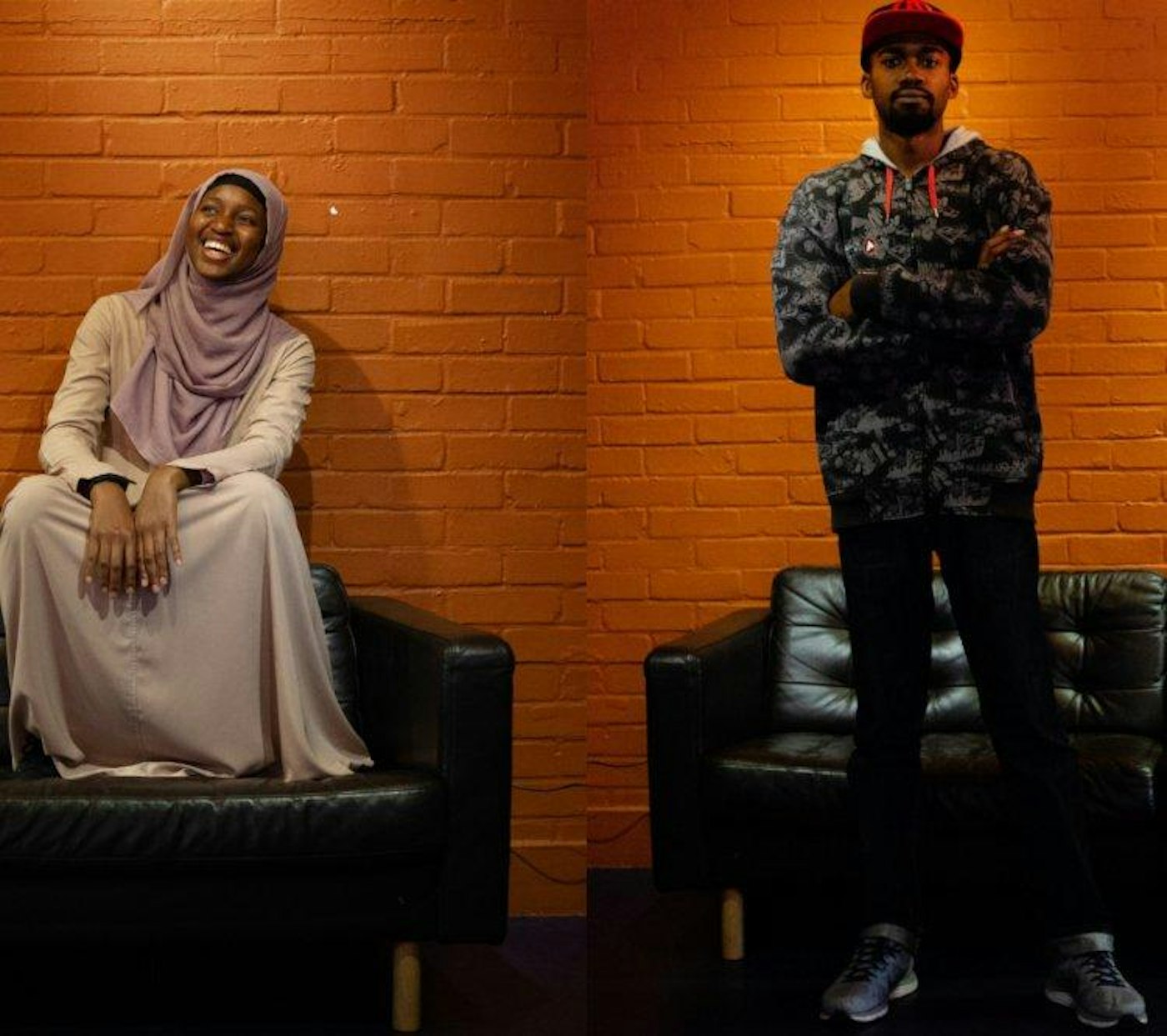

Credit: Stagedoor, Amina Koroma (left) and Emmanuel Simon (right), members of Ovalhouse Young Associate, June 2019

In the first instalment of Amaliah’s breakout women in film series, Black British actor Amina Koroma speaks to Adama Juldeh Munu about her experiences in the voice acting industry and how she reconciles visibility and representation as a ‘sister behind the mic.’

From video games to animation and audiobooks, 29-year-old Amina Koroma has had a busy few years making her mark as a screen, stage and voice actor.

Koroma is a British-Sierra Leonean who started out her career as an architecture student at a prestigious arts and design school. She was inspired to embark on this path because of a US-based programme, ‘Extreme Makeover: Home Edition’ and her love for Afrofuturistic architecture. In fact, one of her heroes is a Burkinabe-German architect, Diébédo Francis Kéré who was responsible for Baobab-inspired towers exhibited at the 2019 Coachella festival. So what took her from architecture to the fascinating world of acting? I spoke to her to find out.

Before we speak about voicing acting… why stage acting? You were studying architecture.

“Performing arts has been a part of my life since I was young. In primary school, I was the lead in plays like Snow White, Harry Potter and the Lord of the Rings, where I played Dumbledore and Gandalf – very enigmatic characters. It brought joy and humour, but despite my parents’ support for my creative pursuits, I didn’t know that having this as a profession could be a reality for me. I also wanted to be an architect for social good. When I got into university and realised how long it would take to turn this degree into a career, I realised that I don’t have that in me, when in three years, I was doing late nights and bingeing coffee which I hate.

So post-university, I had to take a step back and ask myself what I really loved doing. That’s when I harked back to my childhood and asked ‘Oh what happened to theatre? ‘Why did I stop that?’ So I looked into a theatre company where I auditioned at the Young Vic for the Suppliant Women, and got in.”

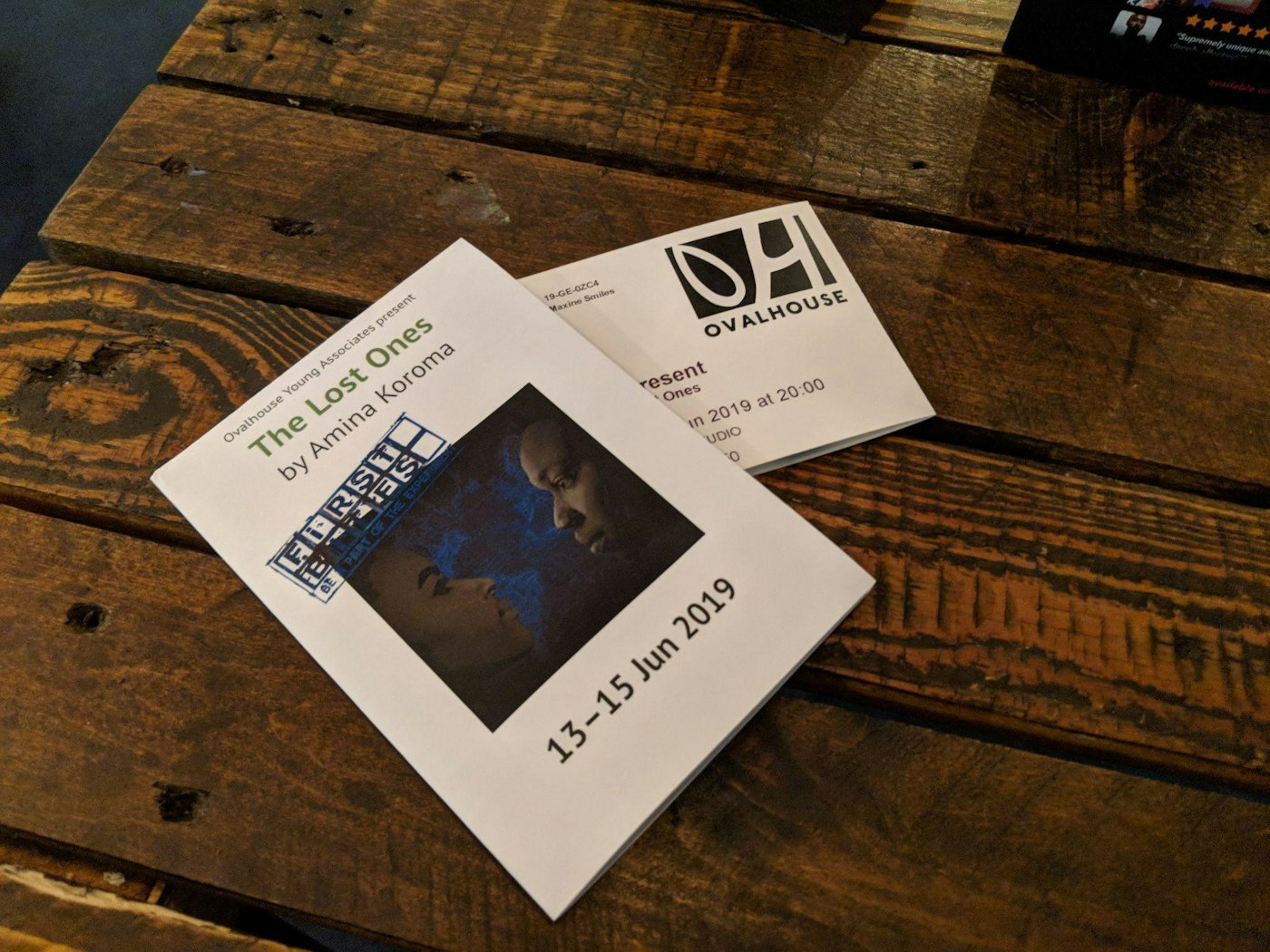

The opportunity – which fell through – opened her up to others such as her work at the Oval House performance company, where she honed her playwriting skills as part of their young associate’s programme. “I wrote and developed a play called ‘The Lost Ones’, which showcased the Muslim experience of the Middle Passage because we don’t get that side of the story. Like how did people maintain ibadah (worship) while on such a perilous journey? The play received good reviews, but because writing is laborious, I didn’t feel like I had the capacity to continue playwriting just yet, but I do have a couple of plays in me,” Amina explains.

Credit: The London Theatre Marathon

So, what got you your first start in voice acting?

“I made that transition right during the pandemic when everything was locked down. Theatre ‘died’ on the spot and television productions ground to a halt. The only thing that seemed to be going was voiceover (work). I found out about it in 2019 through an expo for actors now called the ‘Actors Expo’.

Alhamdulillah, it just so happened that the bonus I got through the Christmas trading period was enough to set up the basics for a home studio, to then start putting myself forward for castings and auditions that I would find on Twitter. If I happened to book the job, I could record without leaving my home or being exposed to anything outside. And that was great because the lockdown happened just when I got my kit in March. I realised I wanted to get into it more, in addition to theatre and screen work. Now I am three years in, (but) I still consider myself an actor in the screen and theatre sense.”

I am curious to hear from you what voice acting ‘is not’, because there are some misconceptions about it, right?

“Voice acting is not putting on voices. People think of it as Looney Tunes.” She then puts on a caricatured voice to demonstrate. “It’s still acting but through the voice. It’s a specialised skill because it has to come from a place of truth. With animation, you (also) have to communicate expressions and movements. We call these ‘efforts’. These are the non-verbal sounds that accompany an action like giving hits or jumping.”

Social media has its uses for Amina. In fact, the first piece of work she booked was an indie video game called Monstrom Two which she found through a casting call on Twitter. Amina has gone on to book other gigs that include voiceover work for animation including HBO’s Primal. She’s also narrated Talia Hibbert’s New York Times best-seller, “Highly Suspicious And Unfairly Cute”. She made her screen debut on ITV’s series Grace last year.

Credit: HBO Max, October 2022

It’s been a particularly difficult time for creatives in the industry though. Since April 2023, there have been protests by creatives in Hollywood over pay and working conditions which Amina tells me affected work in the UK as well.

How are you coping with the strikes and protests? It’s having an effect on the UK, right?

“Voiceover work is the work that is available to me at the moment because of the Writers’ Guild and Screen Actors Guild controversy. The auditioning opportunities have been very slow, and we’re still at the backend of the domino effect of COVID and all these strikes, where the US is the biggest entertainment industry.”

At a time when discussions about visibility and representation are now more mainstream, how do you reconcile your role as an ‘invisible’ actor while being a visibly Black Muslim woman?

“I think it’s a double-edged sword, because, on the one hand, you want to be seen as a full-rounded person. You don’t want to be just associated with isms and labels. But then again, I am a Black Muslim woman, and I am making inroads in an industry that was previously inaccessible to me. It’s funny because sometimes I think ‘I am just an actor’, but when I announce things online and then people put a face to the role, it’s like ‘Oh wait hang on, there’s a Black Muslim woman doing this’.

In the audition process for an animated film, your appearance is not considered, you are judged by whether the voice matches the character and the vision of the creator. More people of different ethnicities are making inroads, and these discourses about ethnic actors voicing ethnic characters do take place. But sometimes being what it is, when you have a Black actor who is voicing a Europeanised character, there will be people who will be up in arms about it and so racist terms are bandied about.”

Amina is familiar with the importance of ensuring the industry has a diverse understanding of what UK casting brings in including different accents, regional placements, ages and classes. In fact, she is the co-founder and operations manager of VO Britlist. The main purpose of VO Britlist is to advocate for British/UK-based actors, granting them access to roles within US productions. This became feasible due to the remote work opportunities that emerged during the pandemic, allowing the inclusion of authentic British voices for characters coded as such.

She tells Amaliah, “I really jumped on it because I was inspired by the People of the Global Majority Voiceover List (PGM VO List) that sprung up in the midst of the Black Square summer of 2020. What happened to George Floyd opened up a Pandora’s box for the Black Lives Matter movement and off the back of that, there was a drive for non-white actors into this field. Yes, there’s diversity on the screen, but we need people from those communities behind the screen. I wanted to help build a British equivalent. If you think that the acting world is small and cliquey, voice acting is even more so, to the point where the major production houses only go for people who have agents. There’s so many barriers and for people who are very talented but had an unorthodox way of getting into the field, the lack of an agent could be a barrier that stops them from thriving.”

This all sounds very exciting, what advice would you give Muslim women interested in voice acting?

“Investigate first if you see yourself in this for the long term. It requires considerable financial investment and time commitment, which is quite steep at the beginning, including but not limited to paying for headshots, memberships, classes, training, and setting up your own studio. Are you committed to making this a primary or secondary source of income, as there can be pitfalls along the way?

If it’s something that you want to dabble in, you can research local theatres, some of which have schemes and give people the opportunity to join shows. There might be an acting academy or workshops as part of show programming. Sign up to their mailing list and see what’s available. Just show up and have a go.”

Adama Juldeh Munu

Adama Juldeh Munu is an award-winning journalist that's worked with TRT World, Al-Jazeera, the Huffington Post, The New Arab and Black Ballad. She writes about race, Black heritage and issues connecting Islam and the African diaspora. You can follow her on twitter @adamajmunu