Unimagining Muslim Women – The Spurious Art of Representation

by Mariya bint Rehan in Culture & Lifestyle on 16th May, 2023

There is very little Muslim women, in particular, have gained from the spurious art of being ‘represented’ in the media. In film and TV it has given us the unironically crafted character arc of being abstractly, and totally inexplicably ‘dehijabed’ as a means of self-discovery and joy. There are scant few Muslim women on screen that aren’t liberated by a mediocre white boy with a just-broken voice and boy-band hair whose super power appears to be depinning head cloth and inhibitions. Representations in literature remain honourably loyal to the age-old ‘behind the veil’ trope with its strong allusions to an ‘Arabian Nights’, heavily kohled, air thick with smoke, musk and mysterious flutes kind of vibe. Bless. And of course, in advertising we can’t seem to divorce our long-standing friend, and humanising accessory that is the skateboard. Because Muslim women on wheels are more deserving of empathy and praise than when we come detached from our sporting prop.

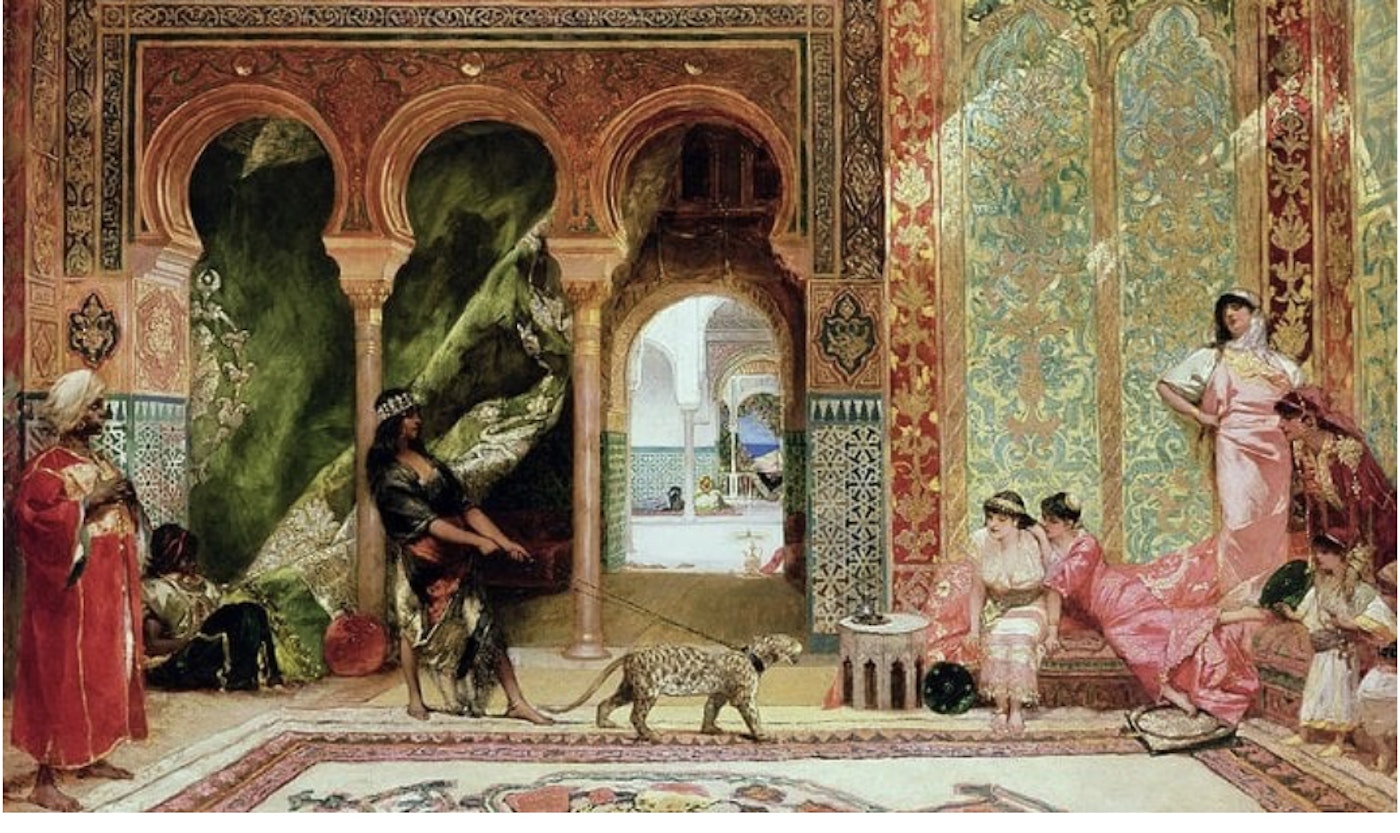

The sometimes obsessive act of ‘reimagining’ the Muslim woman by those that aren’t her is fraudulent in nature. In early orientalist art, with work going as far back as the early 19th century, the painterly gaze of artists from Europe and North America who depicted the Middle East and North African world as lands of ‘beauty and intrigue’, hit a frustrating wall when it came to Muslim women. Seeing Muslim women as an extension of the land they sought in conquest, they often depicted the women they were restricted from viewing in their work. Often their curiosity and lustful eyes would lead to fantasy depictions of the harems that so ignited their interest and which were so out of their visual reach.

These earliest portrayals of Muslim women were rooted in nothing other than the Western imagination of a hidden and unfathomable world; they are mirrors to those surveying men, and not windows into the lives and beings of their subjects. In fact, they have nothing to do with Muslim women, and totally ignore their reality. In this way, they speak more of those that are trying to imagine than those they attempt to conceptualise. Since this early practice of ‘imagining’ the Muslim woman, we have had a barrage of equally criminal ‘reimagining’ of Muslim women built upon and in response to this falsehood, and ultimately, someone else’s ego and vanity.

The Muslim woman as a prop for others’ sense of cultural and intellectual superiority is the common thread that unites this circus of caricatures that are dotted through western visual culture and history. All in the name of representing the unrepresentable.

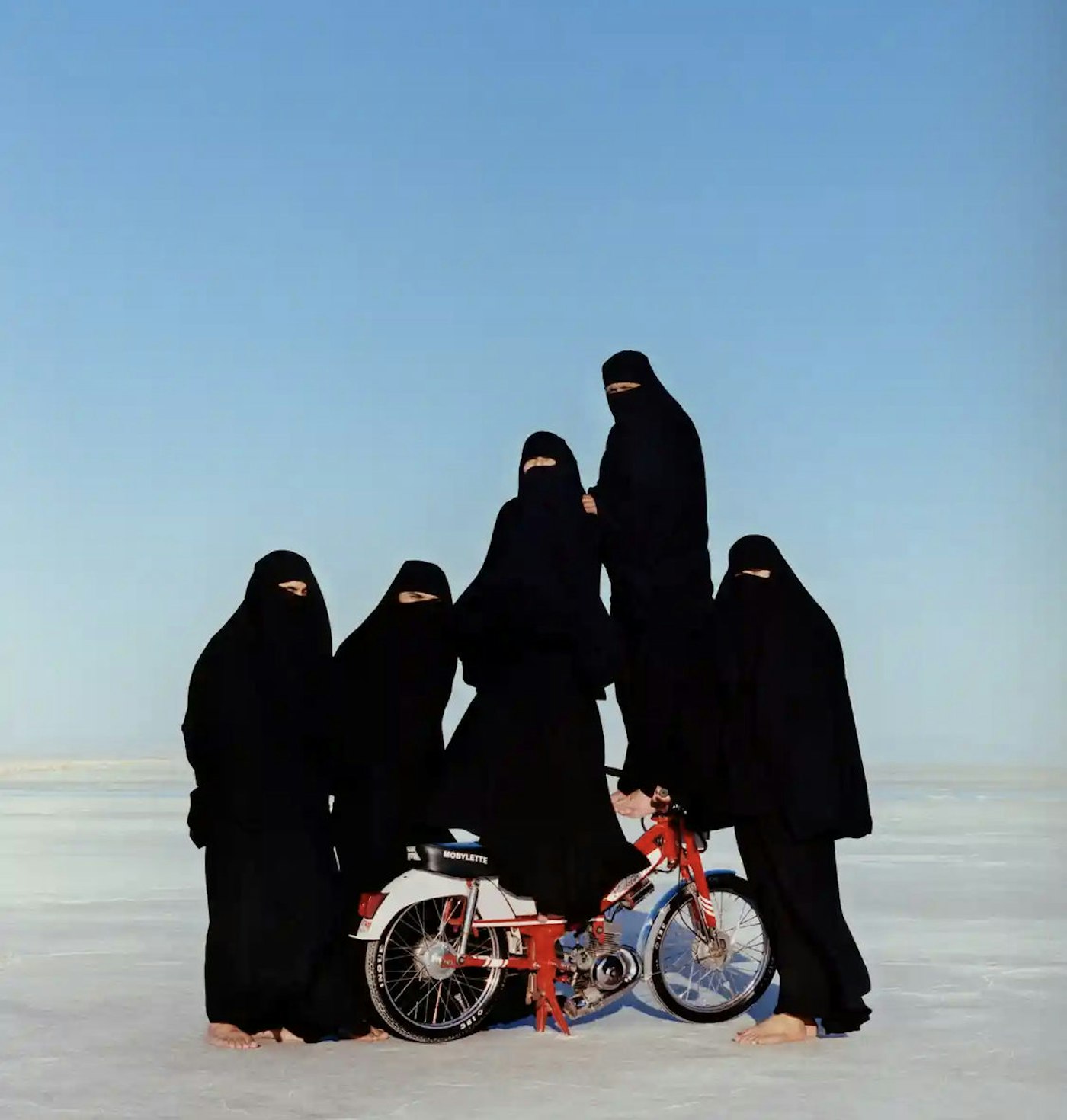

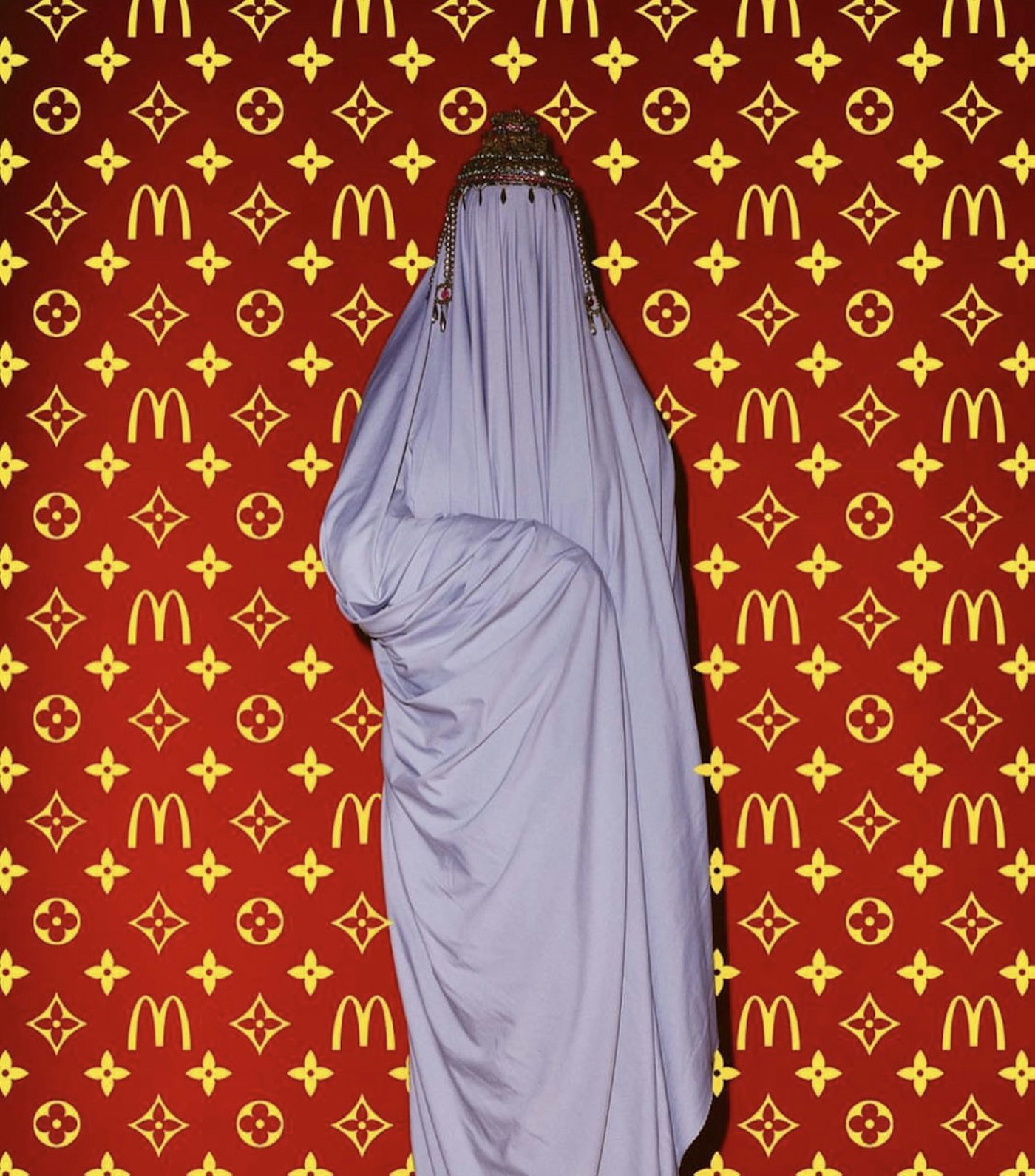

Amongst the most frustrating of these genres, and the one which exemplifies this ballooning trend as charlatan in nature, is the ‘high-art’ world of photography which claims to use a post-modern, self-referential irony to subvert this dehumanising trend. The supposedly dissenting image of the darkly veiled, often niqabed, Muslim woman juxtaposed with some wildly annoying, superficial reference to ‘modernity’ as a statement about Muslim women not fitting a ‘stereotype’ is so tired and recycled, that it has become an acceptable, and lazy, shorthand for a seditious art supporting us.

It embodies the most obvious and insulting ‘Muslim woman as submissive, voiceless object’ trope to make some supposedly tongue-in-cheek commentary about the art world. This art ‘knowingly’ claims to be the mirror and not the window, though the results and impact remain frustratingly the same – an entrenching of visual and symbolic tropes which objectify Muslim women and which provide a smug, self-congratulatory satisfaction to the audience who ‘get it’.

If visual media plays architect to our cultural values, this constant barrage of imagery which paints the Muslim woman as subdued and subordinated does nothing to challenge the harmful assumptions regarding us, nor the material realities that underpin and reinforce it. It is effectively adding to a dumping ground of negative imagery associated with Muslim women and does nothing to move us forward culturally. In claiming to be disruptive, it reduces our worth to a symbolic opposite of a specific idea of ‘modernity’. The Muslim woman is further objectified in the name of her de-objectification and the world of high art sets the visual tone and cultural precedent for representation in all art and media downstream from it. It further cements an infantilising narrative while claiming, in its purportedly visionary and groundbreaking position, to do the opposite.

Worryingly, we as Muslim women have come to accept it as part of our narrative. Tellingly, these images are overwhelmingly photographed and directed by men, and those that do not identify as Muslim. Their proximity to Muslim women – either as Muslim men, or hailing from a Muslim background, means they can to all intents and purposes, position themselves as allies, and their visually regressive work a clever act of solidarity. Often it is seen as a kind of benevolence, as though a mere reference to our continued dehumanisation is enough.

Its special trick is to bring the ‘subtext’ of how Muslim women are regressively portrayed, to the very surface. It claims by directly visually referencing our subjugation – in simply foregrounding and ‘ironically’ engaging in this reductive symbolism of false representation of Muslim women – it is doing all the muscle work of exposing and deconstructing these stereotypes. Due to its modern, ‘edgy’, often urban or faux-parochial-twee aesthetic it is accepted as a ‘minority’ perspective – in as far as minority perspectives are understood – and is therefore automatically given the rubber stamp of ‘authenticity’ and speaking on our behalf.

It commands respect both due to this supposedly subversive look and nature, and in how unabashed and obvious it is – the inverted logic that the idea of putting a niqabi woman on a bike/holding a boombox/covered in a corporate logo is so obviously insulting, it has to be supportive? It’s so shockingly rude, and saying the quiet bits out loud that it must be trying to make a point. Right?

This is part of a broader trend in the art world, made up overwhelmingly of those from privileged backgrounds, in which the symbols of the ‘oppressed’ or ‘disadvantaged’ are used in crude and shocking ways to make vague and nebulous points. By employing a shallow symbolism, this trend seems to further that oppression, while claiming impunity for being ‘socially conscious’ or ‘aware’. It is also a symptom of a more niche trend that exists amongst artists of a Muslim background. Many of whom gain popularity and currency from their secular identity and viewpoints in their homeland, while simultaneously depending on their Muslim identity to gain ‘diversity’ points and get their foot in the door in the West. This raises some pertinent and much needed questions about what passess as ‘acceptable’ identities, expressions and subjects in the global art world and why.

What do we feel comfortable viewing in sanitised frames, in our clinical galleries, and what does this say about our need for affirmation, and our generosity in extending understanding and solidarity?

These postmodern era representations of Muslim women are problematic for a number of reasons beyond just the sheer gall of using Muslim women as objects of juxtaposition. Just like advertising, broadcast and literature, this constant ‘rediscovering’ of the Muslim woman as human – having agency, complexity, whim and will, beauty and humour – done safely from behind the lens assumes a default audience position of seeing her as less so. It already sets the tone by which it wants to arrogantly act as a resistance to; the conceptual frame it puts Muslim women in is one of a submissive, static and one dimensional stereotype. In constantly ‘rediscovering’ Muslim women, it pushes us further away from the signified ‘human’. It does nothing to advance a conversation which seems to be stuck on the surprise element of the Muslim woman as agent. This constant revisiting of the Muslim as anything other than an insentient, pliable being reinforces the assumption that she is so. It assumes very little of Muslim women to begin with, and works lazily from this vantage point alone.

It continues a centuries-old conversation with the viewer – this time, rather than crafting and pandering to the ignorance of the audience, it gives it a knowing wink and nudge. This trend is not some altruistic gesture working to humanise Muslim women and launder their public image – and that’s even before we address the binary code it endorses. Rather, this artwork is self-indulgent, attributing humanity to the consumer of this media. It tells the audience they are generous for understanding, being in on the joke.

Once again, in continuing a tradition dating back to the birth of orientalism, it gives the audience, the surveyor, those that are doing the ‘perceiving’ the upper hand – it attributes superiority to them because they may be able to conceive this as a false representation of Muslim women. It is congratulating an audience on the bare minimum of being able to potentially envision Muslim women outside of a narrow and constricted stereotype – not actually attributing anything of substance to Muslim women outside of it. It is the art world equivalent of your, otherwise respectful, elderly History teacher telling you not to worry, he knows Muslim women can be ‘modern’ or reassure you that he knows not all of you wear that silly thing on your head – it assumes very little of the hijab itself, reducing it to a barrier for male consumption, and using it as a symbolic ‘other’ to modernity. Once again Muslim women are not part of, nor do we want to have anything to do with, the rambling and incoherent conversations between one man – in this case the paternal and aging art world – and himself. What is painfully telling is that most Muslim women do not in earnest engage with this suffocatingly limited paradigm. We do not base our understanding of ourselves or our faith on such ridiculously poor assumptions.

The idea of ‘representing’ Muslim women is erroneous because there is no homogeneity to represent.

The hijab itself as separate to us as women and as an expression of our beautiful faith remains something that will be alien to an external agent – be that men or non-Muslims – and which will resist the net of social, cultural and anthropological definitions or expressions. One of the many and Divinely set functions of hijab is to act as an equalizer – there is beauty in its democratising nature that is hard to discern in a world of mass consumerism and the hyper individualism that it breeds and feeds off. The hijab is not anchored in a value system which privileges a superficial beauty or the charms of fashion, and its notion of exclusivity or being ‘seen’. Like Islam, the hijab demands more of us, intellectually and morally. And that is no bad thing.

For an edict that we are blessed to have been sent directly from Allah, it becomes impossible to discuss, analyse or dissect on any other terms than from Islam itself. The tools, language and experience of ‘representing’ hijab – be it visually or through other forms of media and literature – do not exist because it is Divinely ordained and therefore unfathomable to those that don’t share that faith or experience. The problem isn’t with the hijab, the issue lies with the very flawed nature of representation in a world that doesn’t understand the beauty and sincerity of faith. The issue is the act of representation itself. Perhaps we would be better off dissecting, analysing and foregrounding this obsessive act of representing, of being able to fit neatly into a conceptual box, and what this says about our own self-flattery and ego, our own attempt to colonise knowledge and understanding in a world created by His Majesty.

In a world of Only Fans, ubiquitous cosmetic enhancement and a titanous beauty industry, the act of covering, and modesty as an endeavour, remains radical in the most unparallel of ways. When we are encouraged to share, reveal our inner and outer world, the quiet act of keeping something to yourself will always defy understanding. Islam in itself is iconoclastic, it came and rebuked traditions and continues to defy and rebuke traditions today. As half the world continues to argue that the hijab is a tool of patriarchy furthered only by men, while the other half argue condescendingly that it is modern as though this is a qualifying feature, the truth remains that the hijab, and most women who have the privilege of wearing it, is centring Allah and not men, society, nor the concept of modernity. As women are encouraged to dress, redress, shape and reshape themselves in line with a standard that revolves around the male vantage, and changing fashions, the hijab and niqab will always remain a thing of curiosity and astonishment. This idea is simple not one that the art, corporate, literary or media world has the range to cover.

Mariya bint Rehan

Mariya is a 33-year-old mother of two young girls with a background in Policy and Research and Development in the voluntary sector. She has written and illustrated a children’s book titled The Best Dua which is available internationally and in the UK. IG: @muswellbooks