How a Muslim Artist Uses Abstract Art to Illustrate the Soul

by Adama Juldeh Munu in Careers on 10th February, 2023

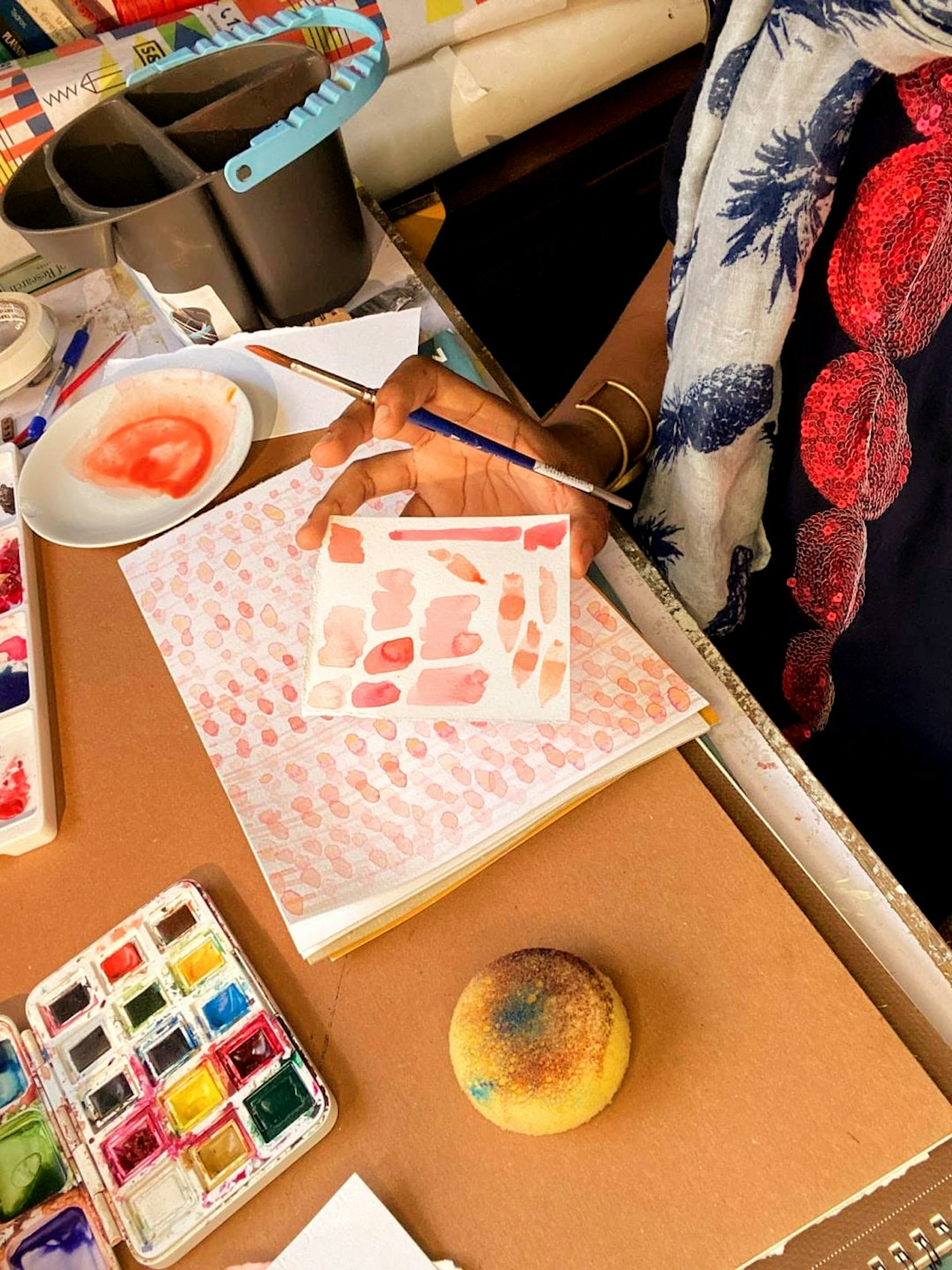

Nsenga Knight working on the Fitra: Amber series

In Islam, the belief that it is the natural disposition of human beings to worship the Creator and to incline toward what is good and wholesome and to stay away from what is not is described as fitra. It is an intrinsic part of the Islamic creed or aqeeda to believe that every human being was born upon it. The Prophet’s companion, Abu Huraira (ra) narrated that the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) said, “No child is born but that he is upon natural instinct. His parents make him a Jew, or a Christian, or Magian. As an animal delivers a child with limbs intact, do you detect any flaw?” Then, Abu Huraira recited the verse, “The nature of Allah upon which he has set people.” (Surah Rum 30:30) [Sahih Bukhari 1292]

That belief in the ‘abstract’ and its tangible manifestations of worship is the inspiration for a collection of watercolour portraits by US-based multi-disciplinary artist Nsenga Knight. Nsenga’s photographs, paintings, drawings, and collaborative social practice references Islamic ritual and cosmology, Black history archives, and personal memoirs.

She was born in Brooklyn, New York City to parents who emigrated to the United States from the Caribbean and South America in the 1970s, and who as teenagers converted from Christianity to Islam. Fluid transitions between places, philosophies, and histories like this have developed her understanding of the visual world – its nuances and boundaries, and the need to resist, reevaluate, and push.

“Contrary to the Christian faith my parents were raised in, in the Islamic faith they converted to – there is no concept of original sin. On the contrary, as a child, my parents taught me that according to Islamic teachings, all people are born pure and without sin. This pure nature is our fitra and it is key to our connection to our Creator and our divine purpose. Our fitra is our most “authentic” and natural state,” Nsenga tells Amaliah.

Nsenga Knight working on a piece from Fitra: Amber series | Source

Last year Nsenga was one of three artists chosen for a two-year In Situ Artist Fellowship at the Queen’s Museum studio in New York City. For her fellowship, she chose to use abstract art to explore the soul. She delves into why some of her work is fixated on the ‘unseen’. She tells me, “There is a relief in a sense that everybody in their essence still has this ‘thing’ that’s inside of them, that they can return to. In the West, we are concerned about the body. There’s this idea that if you fix your body, you can fix your problems.”

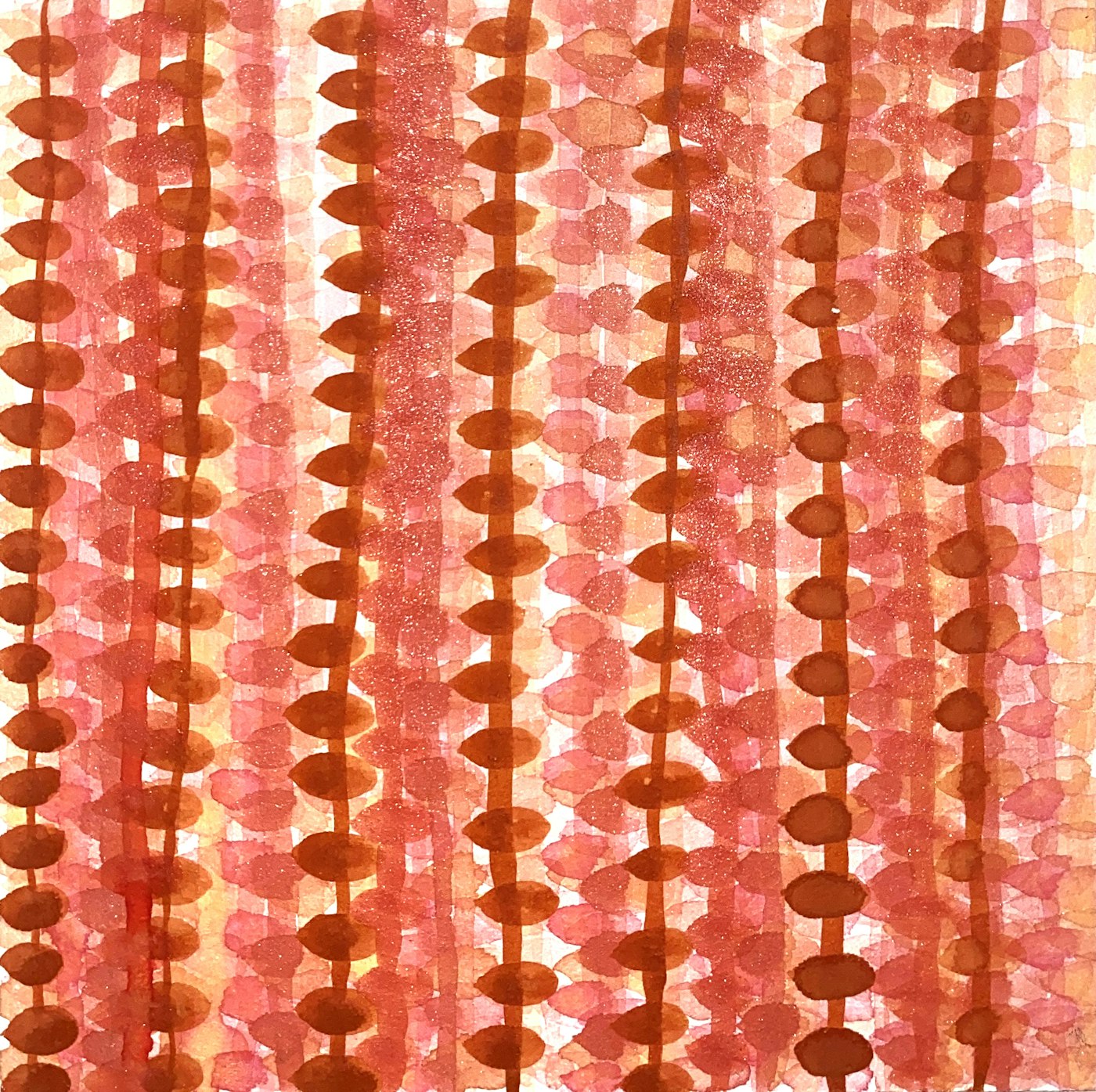

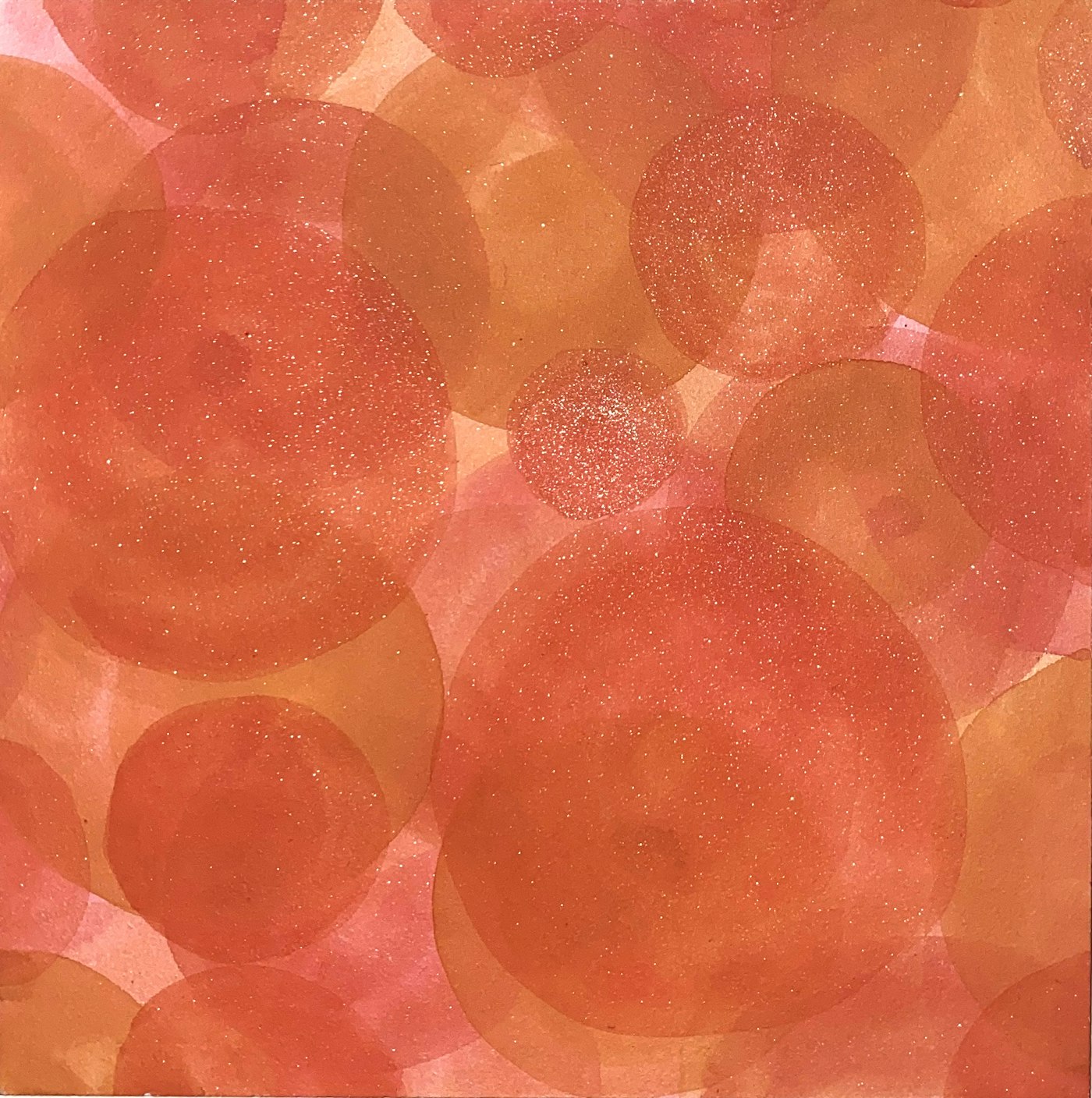

Credit: Fitra/Amber Series, Nsenga Knight

The ‘Fitra: Amber’ is the first instalment of a series of seven watercolour pieces primarily inspired by a chapter, ‘The Soul of the Rose’ in the Book of Sufi Healing where author Abu Abdullah Ghulam Moinuddin recalls a story of the King Prophet Sulayman (Solomon) who is greeted by amber, and which tells him its name and its purpose in healing.

“Humanity came to learn about the healing properties of plants as each one revealed its special properties to the King Prophet Solomon who later passed down this knowledge for generations to come. Amber is known for its spiritual and physical ability to heal our hearts… Like a seed of any plant, it is only through breaking ourselves open and allowing ourselves to shift and be transformed that we reveal our highest purpose, express the best of who we are and share our unique gift with the world,” Nsenga explains.

The series also breaks away from some of her previous work that’s focused primarily on ritual and documentation of the Black Muslim aesthetic in the US. These include her photography series ‘As the Veil Turns’ which showcases Black Muslim women who converted to Islam prior to 1975, a pivotal year as it marks the death of Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam. Her 2013 exhibition ‘Ritual and Revolution’ utilises forms found in pilgrimage rituals, sacred geometry and classical astronomy that bind together ideas on social justice, ritual and dialogue of the Iranian revolutionary and sociologist Ali Shariati’s memorable reflections on the symbolism of the Hajj, and Abu Rayhan al-Biruni’s 10th-century astronomical analyses.

Credit: Fitra/Amber Series, Nsenga Knight

Amber is one of the healing plants discussed in the Book of Sufi Healing and has been grown and utilised in various parts of the Muslim world including Tunisia, Sudan and Afghanistan, as well as the Dominican Republic and Russia. The oil of amber or kharabah as it is known in Persian is grown from a type of pine tree known as Picea Succinfera. The oil in the tree’s sap is preserved for millions of years and is considered a source of ancient healing energy, according to the book.

Credit: Fitra: Amber Series, Nsenga Knight

Since ancient times, amber was known and valued both by the Persians and Arabs. Persian scientist Ibn Sina (Avicenna) called amber a remedy for many diseases. In some Middle Eastern cultures, there was a belief that amber smoke could strengthen the human spirit and provide courage. In China, “amber syrup”, which is a mixture of succinic acid and opium, was used as a sedative and as a means against spasms.

Credit: Fitra: Amber Series, Nsenga Knight

Nsenga brings to the fore the relationship between prophethood, healing and nature by suggesting Prophet Sulayman was in tune with plants, nature and beauty. His story with plants in the chapter ‘The Soul of the Rose’ inspired her to look into the relationship between medicinal flowers, oils and the natural disposition of human beings with passages such as: “This notion of an absolute essence also applies to the human being in relation to the soul. This intimate relationship between absolute essence and manifold forms of that essence is duplicated in all of nature. Each flower, tree, and shrub has its physical form and also its essence. For instance, the seed of oak will not produce a willow,” and…

Credit: Fitra: Amber Series, Nsenga Knight

“Amber has been fossilised for so long that we even have no way of knowing what other life forms were present. But we do know that the prophets who lived long ago had extraordinary powers of perception and healing. It is said, for example, that one prophet was able to overhear a conversation of ants, at a distance of more than ten miles! It is likely that in addition to being endowed with spiritual powers, they had hidden knowledge of healing plants. Many of these species are now extinct.”

Credit: Fitra: Amber Series, Nsenga Knight

Her children and memories of her childhood are important focal points for how she manifests amber through different shades and patterns across each piece. That connection is reflected in the fluid, transparent and ‘child-like quality’ of the art. “ I use the same colours repeatedly in unique ways to express the various possibilities and shifting purposes that even the same colour can hold. I painted in watercolour because this is the first art medium I recall learning as a child. Each painting is named after a child in my family – (including) my own nieces and nephews. Children remind us of our fitra – the great potential, and pure and special nature that we all have,” Nsenga says.

Credit: Fitra: Amber Series, Nsenga Knight

The Amber installation is an introduction to Nsenga’s reimagining of the natural disposition of humans, and how returning to that is a source of healing. The other series will go through the ten different healing elements in plants that are discussed in the Book of Sufi Healing. The next installation will focus on violet and its expressions across different forms, shades and hues.

Adama Juldeh Munu

Adama Juldeh Munu is an award-winning journalist that's worked with TRT World, Al-Jazeera, the Huffington Post, The New Arab and Black Ballad. She writes about race, Black heritage and issues connecting Islam and the African diaspora. You can follow her on twitter @adamajmunu