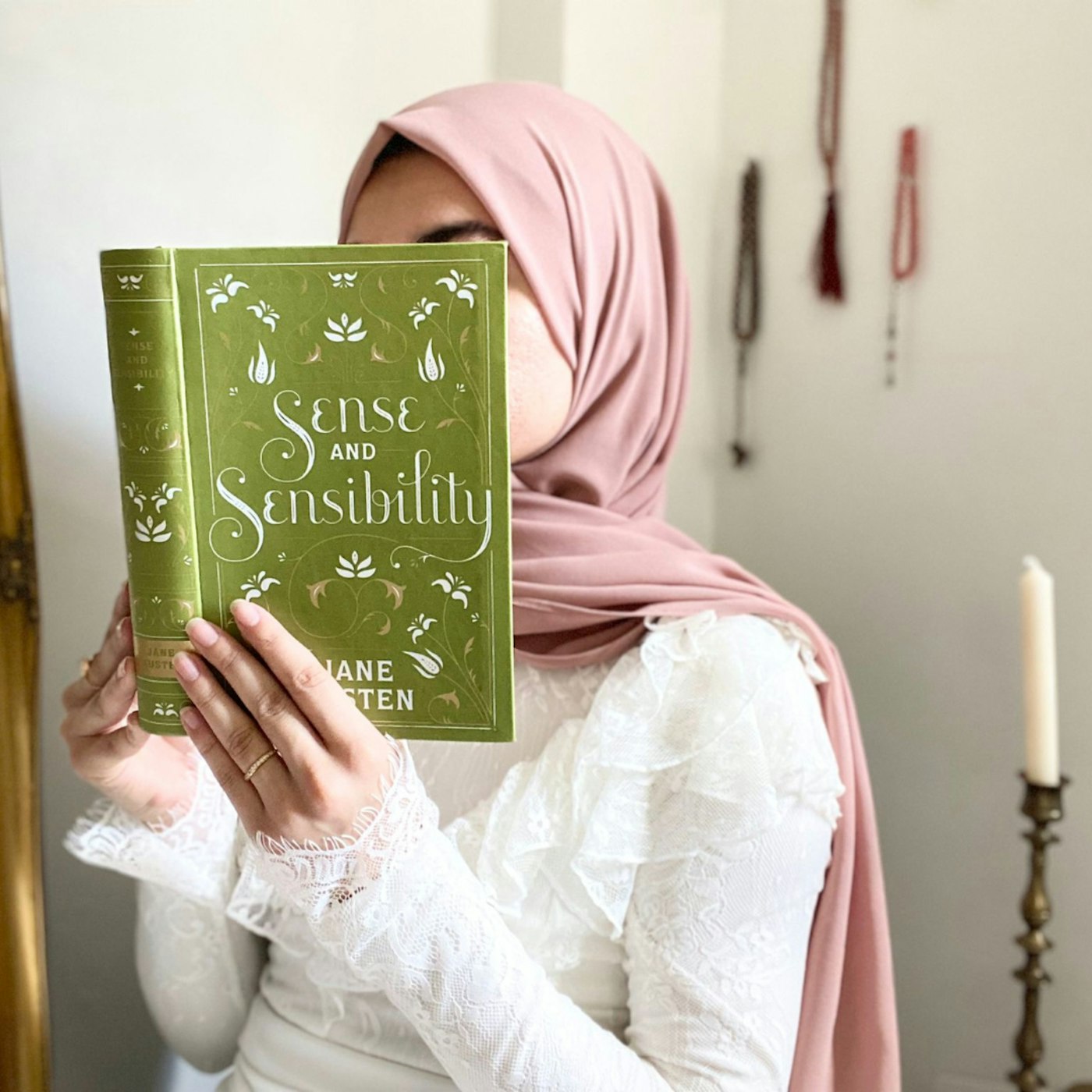

What Draws so Many Muslim Women to Jane Austen?

by Syraat Al Mustaqeem in Culture & Lifestyle on 3rd October, 2022

Literature enthusiast Syraat Al Mustaqeem takes a deep dive into the world of Jane Austen adaptations to understand why so many Muslim women are drawn to her stories – while some hold reservations.

I have a deep appreciation for attempts at reincarnating old Austen tales – absurd adaptations like ITV’s Lost in Austen were my bread and butter growing up. But, as it turns out, there seems a greater chance at appealing to the two-and-a-quarter-century-strong fanbase through full commitment. Modern takes like Clueless (1995), Bridget Jones Diary (2001) and Bride and Prejudice (2004) have stood strong for their adherence to the centuries they chose. Rosie Rushton’s 21st Century Jane Austen series, which were rare finds at my local library, also captured the essence of a bookish tween romance without speaking down to the young audience. But Burr Steer’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016) should have been warning enough that some modern elements fall flat in the face of coattails and silk gloves.

between netflix’s persuasion, sanditon’s demise and this tweet, do you think jane austen is resting peacefully? https://t.co/6uROzDte0c

— enola holmes updates (@covisnky) August 15, 2022

Unfortunately, the confident stab at a millennial dialect in Netflix’s take on Persuasion had not learnt this lesson and fell short among – well, a lot of people. Again, this is not just the consensus of purists but fans who would agree that the cringy dialogue (Anne’s younger sister branded an “empath” and the dreaded: “If you’re a five in London, you’re a ten in Bath”) would be a painful distraction in any rom-com.

Like any bad translation, Alice Victoria Winslow’s recent screenplay takes the widest definition of the word, turning Persuasion to Influence(r).

So, with the many good (and the increasingly disappointing) versions of cultural classics, what is the constant pull that keeps us coming back to the source? You could say it’s the slow-burn, enemies-to-lovers trope of Darcy and Elizabeth that first pulled in pre-pubescent romantics (it me). Or flowing dresses and the God-granted power to engage only when you decide so. But as a Muslim girl who had these elements at her fingertips, this wasn’t new. Every romance I’ve had has been (painfully) gradual with moral barriers to interactions with the opposite gender; every dress hung past my ankles; and the choice to engage always lay with me. I found more in common with a meddlesome Emma, who learnt her lessons about gossiping the hard way, than young Disney stars who were dating by 13 years old. And I was far from the only one.

A phenomenon I’ve seen among many Muslim women is this love for Regency works.

Jane Austen’s (and often the later Brontes) dignified standards, the boundaries of courtship and the floor-length capes are all factors that, at a glance, align with the Muslim identity. And at the early-teen stage where the definition of femininity was in flux – back when Barbiecore was strictly for toddlers and Avril Lavigne-esque skater girls were all the rage – it was a time-tested source to see an acceptance of varied, feminine, bookish, woodsy and rounded characters.

I sought to find others like me by speaking to some Austenites I met after infiltrating a Muslim women’s book club. Umariah Farooqi, 39, who works in IT, said she first discovered Austen in her early teens after her sister began reading the novels first.

“I always loved the sweetness, the cleanliness and the light romance – and this kind of humour which you don’t get with some of the books of that era,” the mother of three, said.

“I could also relate to the feminine aspect of it – a lot of the stories were about sisters. There was always a character in her books who I could say, ‘I’m this one and my sister is this one’. And I never felt that I wasn’t seen in the audience because the culture in those days was very similar to my culture, where women were at home, they had to marry well – a lot was said on the topic on marriage, on what to do and what not to do. It always felt very, very relevant.”

Leaning more heavily into the wider following that Austen had posthumously attained, women under heavy expectations became the ideal candidate for adaptations. Bride and Prejudice mirrored Mrs Bennet’s obsession with marriage through the constraints of an overbearing Indian mother and maintained class disparities with the added layer of racial divides. And the genre has only become more niche, in a mainstream understanding, with some successful Muslim-centric novel adaptations.

Yet, another book clubber Sana Kidwai, who was grew up in Wales, was completely opposed to this idea. She said: “I’ve never been interested in the bonnets and breeches genre at all, but what I like about Austen is the wit of it.”

“I don’t see myself in the Regency era, but I don’t choose a book because I’m looking to find myself in it. But do I see myself in her novels? Absolutely. You see people you know in her characters. I’ve always based it on personality and character, not as a young woman expected to get married – because that was never an expectation on me.”

“If you look at it at a superficial level it’s very easy to draw this parallel between modest, restricted women who are out to get married. But Austen champions women who are intelligent, who are outdoorsy – they get tan and muddy. There’s a culture of expectation but that’s not necessarily who she champions.”

Pondering the newer versions, Kidwai said: “My favourite adaptation would be the 1995 Persuasion, a beautiful melancholy novel that was captured really well – because it’s not that shiny, obvious romance like Pride and Prejudice, like Emma. And did I mention Clueless? It had all the wittiness and spark that Emma has. But I think all the other adaptations of Emma blur in to one.”

But a younger me didn’t think too critically about the origins of these old tales. Now, the veneration of a white British author, whose setting was complicit in the oppression of people much more like me than a Regency woman, does not sit as well.

Soniah Kamal, author of Unmarriageable, wrote her own post-colonial version of Pride and Prejudice set in a “culturally specific” Pakistan, with an Alys Binat and a Mr Darsee taking the places of Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy. As a lifetime member of the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA), she shared an expertise, from her home in Georgia, of an Austen that was not as empowering as I once thought. Through our conversation, it became clearer that it may be the limits rather than the freedoms that aligned with our settings.

“Both Pakistani culture and English culture, per se, mirror each other a lot in class and status consciousness. And I think that’s what spoke to me about Austen’s works,” Kamal said.

“[Elizabeth] is expected to perform as part of a community and society and family. And I think a lot of women from communal cultures and patriarchal cultures tend to struggle with that. Where does the individuality begin and end versus where does our loyalty or expectations to a community or religion or certain values begin and end?”

Digging out her very first Pride and Prejudice leather-bound hardback, gifted to a 13-year-old Kamal by her aunt, she described how her interest in the genre was not immediate – and not as simple as a Regency obsession.

“I opened this book, I read the first sentence and I was like ‘I’m not reading this’,” Kamal said.

Novels of the era, however ideal for romances, did not pique the Pakistani-American author’s interest until she understood them for their social commentary. For this reason, Unmarriageable’s parallel retelling deliberately clings to its source to reclaim the English classic and rewrite parts of Kamal’s own past.

“I’d grown up in Saudi Arabia so I was in an international school. Because of the nature of this, where everything was being imported, there were books from everywhere. I grew up reading British stuff like Enid Blyton but also the American Judie Blume and then Canadian writers too. But what I couldn’t find was something that was written in English – my first language – that was set in Pakistan.”

“Very quickly, when I started reading, I would transplant things – like cities would become Lahore and sandwiches would become samosas. I didn’t realise what I was doing was looking for myself – and so I wrote myself in, in many respects.”

Uzma Jalaluddin’s Ayesha at Last takes the cast of characters from Pride and Prejudice even further afield with her Canadian Muslim Lizzie replacement, Ayesha, who meets Khalid, a traditional and devout Muslim. Although this adaptation is not as close to the original version, the universal experience shines through, of parents who worry for their children’s futures; of conflicting values that meet through understanding. It’s always pleasant to see versions of lively Muslim romances, but it’s clear that what Jalaluddin took from Austen is not what Kamal centred.

With each reader and writer, my ideas of Austen and the sub-genre dedicated to recreating her texts became more nuanced. Some saw themselves in the writing through culture, some through personality – and some felt compelled to write themselves in. And as far and wide as Austen can reach, it seems her work is not as universal as I once thought. One may note the severe lack of black female protagonists in many regency works and modern takes. Structural erasure of black people in Britain’s classical history is alive and kicking, so as much as Shonda Rhimes tries, the black female debutante is a character still to be cracked. Perhaps as specific as this genre has become, a few shades further may uncover a whole new market before my Austen fascination dies down.

Syraat Al Mustaqeem

Syraat Al Mustaqeem is a graduate in English and journalist. Her interests include world literature and cinema, magical realism and Islamic spirituality. You can find her on Twitter here (@syraatAM).