‘My Home, My Bari’ the Latest Museum of Home Installation

by Khatijah Ahmed in Culture & Lifestyle on 23rd September, 2022

From ‘supporting artist to young artist’ Anisah Yaminah lets us know that South Asian Muslim women ‘are and have been making themselves known.’

The idea of ‘history begins at home’ is taken in stride by Anisah Yaminah one of the artists who worked alongside Rahemur Rahman to work on the curation of My Home, My Bari. The multi-sensory art installation using sights and textures brings history to life through a representation of the personal living spaces of the British-Bangladeshi community.

My Home, My Bari (village) is the latest installation at Museum of the Home who wanted to decolonise their exhibitions. Following the first successful launch focusing on curry houses in Brick Lane, the second installation follows in seamless sequence on shedding light on the legacy of the East London community 50 years ago. It focuses on the other side of the diaspora-the women.

Anisah is passionate about this particular focus as she says, “females were always being breadwinners by sewing or even acting as chefs in the curry houses … females have always been involved”. The young artists involved in the exhibition received training to interview their mothers, aunts and grandmothers, and sought to tell a narrative of their lived experiences while growing up in London. The women we rarely see represented in the media, galleries and museums now have a dedicated space where they have reclaimed their voice and space in history.

For Anisah, this is her first official project. Joining the Brady Centre, a multi-purpose arts centre in Whitechapel, in 2017, to build her portfolio, she quickly rose through the ranks and is now an official mentor. Her support in the first installation of the project led her to being asked to join the second installation as a recognised ‘young artist’, an impressive feat at her young age.

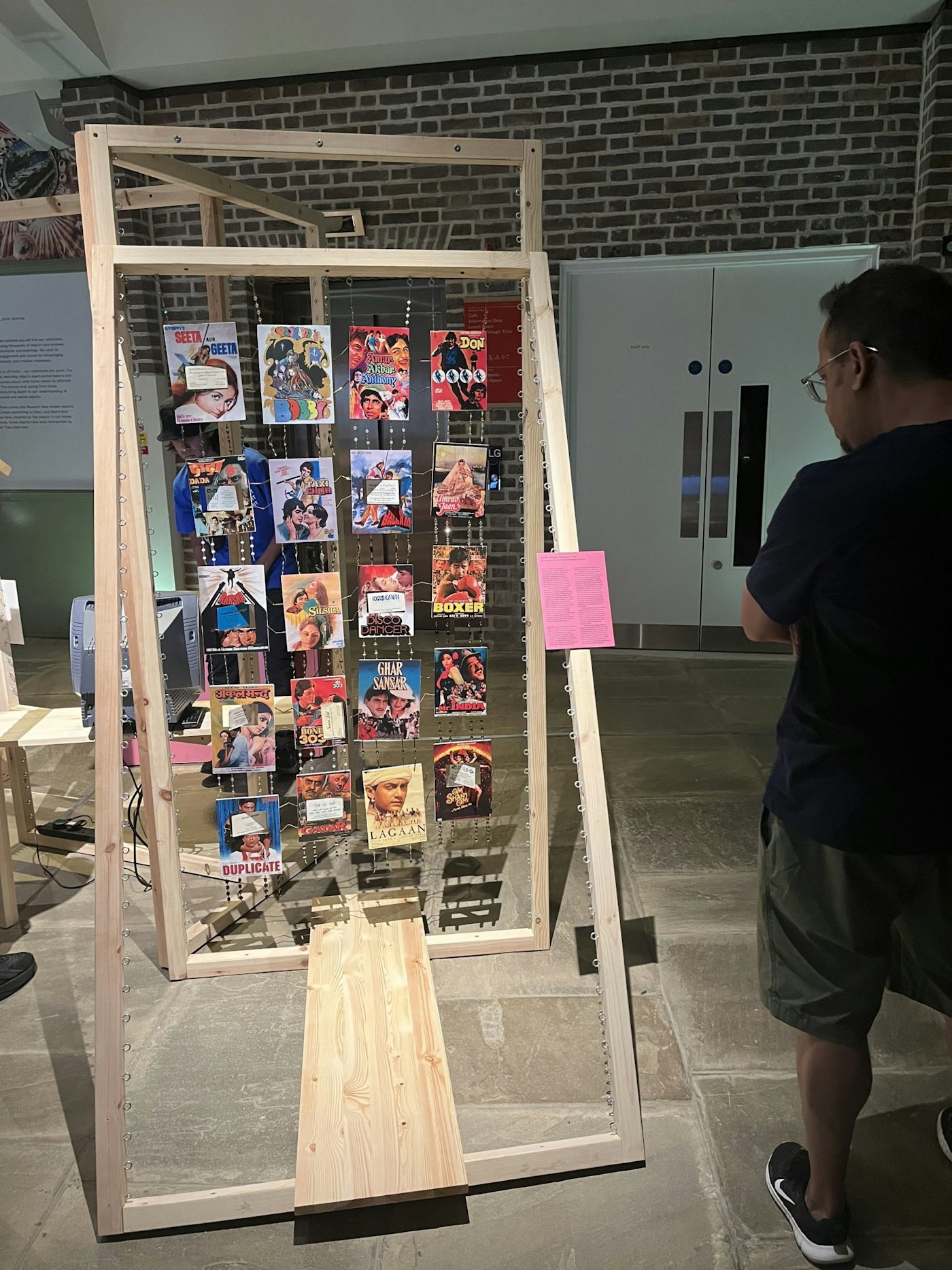

Her wall-hanging installation titled ‘Stillness in Time’, stands bright and proud as an homage to her mother, Rabia Begum and her teenage bedroom. The exploration of teenagehood serves as a gentle reminder that our mothers were once teenagers too, with celeb crushes and the same fangirl behaviour we’re all guilty of. A wall covered in Bollywood posters chronologically of release dates, the joyous installation allows an intimate understanding of Anisah’s mother’s favourite films and what she would have grown up watching at home. Bollywood holds a deeper significance for many abroad. A connection to back home, the timeless musicals are important to many South Asians.

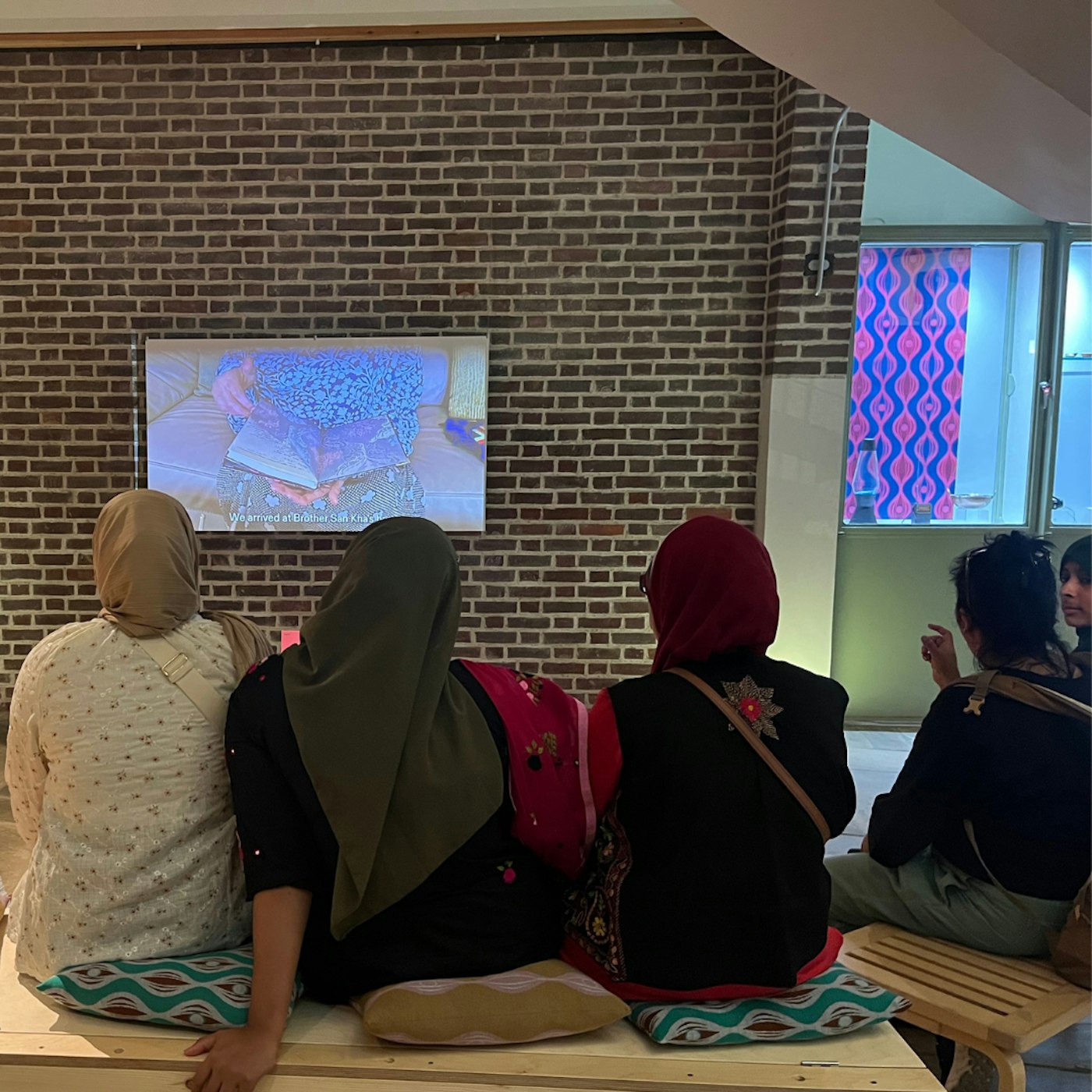

Alongside the installation, Rabia makes her debut in the video interviews that plays throughout the exhibition. The stories told laughingly by Rabia are of her teenage experience in London and the innocent teasing of friends. It is memorable as it remains one of the happier videos with Rabia’s laugh echoing till the very end of the interview. Many of the videos showing different generations describing their stories and experiences moving to London from their baris are quite sombre, making it clear that Rabia is still young at heart as she laughingly recalls her experiences in her interview. It is no surprise that Anisah decided to choose an installation dedicated to the happier times for Bengali immigrants.

Interwoven with the Bollywood posters are business cards that touch upon the theme of communication. Found in boxes when Anisah was moving houses, the business cards are an ode to the Bengali community as a whole. In the process of making London their home, there was an unsaid understanding that if they needed anyone’s particular skill set, the phone numbers on the business card meant help was a phone call away. ‘It was the way families helped each other out and built the community when everything felt strange and foreign,’ Anisah says.

Upon closer inspection, what connects the Bollywood posters are embroidered beads which Anisah dedicates to her mother and the South Asian region as these beads remain distinctive to all regions. ‘I didn’t want an idea that was linear, but instead something that spoke to different people,’ Anisah says. The Bollywood posters, business cards and embroidered beads all mesh into one, speak to different themes and experiences Rabia and countless other immigrants can relate too. The string of beads while initially appearing just singularly pretty mean a lot more to Anisah. A nod to Rabia’s love of embroidery, it emphasises another one of her mother’s hobbies and one that her Nana (Grandad) taught her mother. Anisah reveals that her Nana taught her mother how to embroider and wouldn’t let her leave her room until she knew how to put a bobbin in. This installation led to her mother opening up more about her experiences and childhood. ‘She never really volunteers any information unless we ask,’ Anisah admits. Through this exhibition Anisah has discovered more about her mother and experiences growing up here. She whispers, ‘I’ve seen the VCR tapes, I think my mum was actually kinda cool.’

Anisah credits watching her mother make clothes, which began her love of textiles. From the beginning, Anisah knew that fashion and textiles was the route she wanted to go. She acknowledges her sisters, ‘do what makes you happy’ struck a chord. Studying a BA in Textile Design at Central Saint Martins with a specialisation in weaving, Anisah has always been interested in connecting her heritage to her work. Her previous project was based on the theme of land that she connected to her heritage and focused on the shapes and patterns within Bengali architecture. The dreaded question comes up of what’s in store for the future. For now, Anisah wants to continue this project in another format and has her upcoming final university project which will keep her busy for the next year. She’s ready to delve into other creative mediums such as film and use it to break away from the stereotypes Muslim and South Asian women face. ‘We’re just normal people’, she says exasperated. Her mother’s video portrays that. Full of laughter and joy, Rabia retells happy stories of teasing and walking about East London, that many can relate too.

Anisah and I’s conversation as two South Asian women led to us sharing stories of our parents and grandparents when they came to the UK, connecting to the curfews our mother faced, and our dismay that our fathers may have actually been cool and hip. Her installation highlights the natural way we can focus on the happier parts of Bengali history. It’s not erasing or hiding anything, but an ode to the good times too. The artwork in the exhibition as a whole inspires the current diaspora to ask questions, to focus on the minute details that we may have not thought of before. The unassuming business cards show that with any migration story every detail is precious. Anisah brought a face to one of the brighter installations at the exhibition and it allows me to confirm, Anisah has her mother’s laugh.

My Home, My Bari will remain in the Museum of the Home till October 2022.

Khatijah Ahmed

Khatijah Ahmed is a trainee journalist, who has always enjoyed writing in her free time. Her interests are attending exhibitions and discovering new coffee shops. This year she hopes to write about Muslims making a difference in our community and being able to share that. IG: Khadz2.0