The Accordion Book: On Dala’il Al-Khayrat, Spiritual Muscles, and the Muslim Cosmos

by N.A. Mansour in Soul on 5th June, 2022

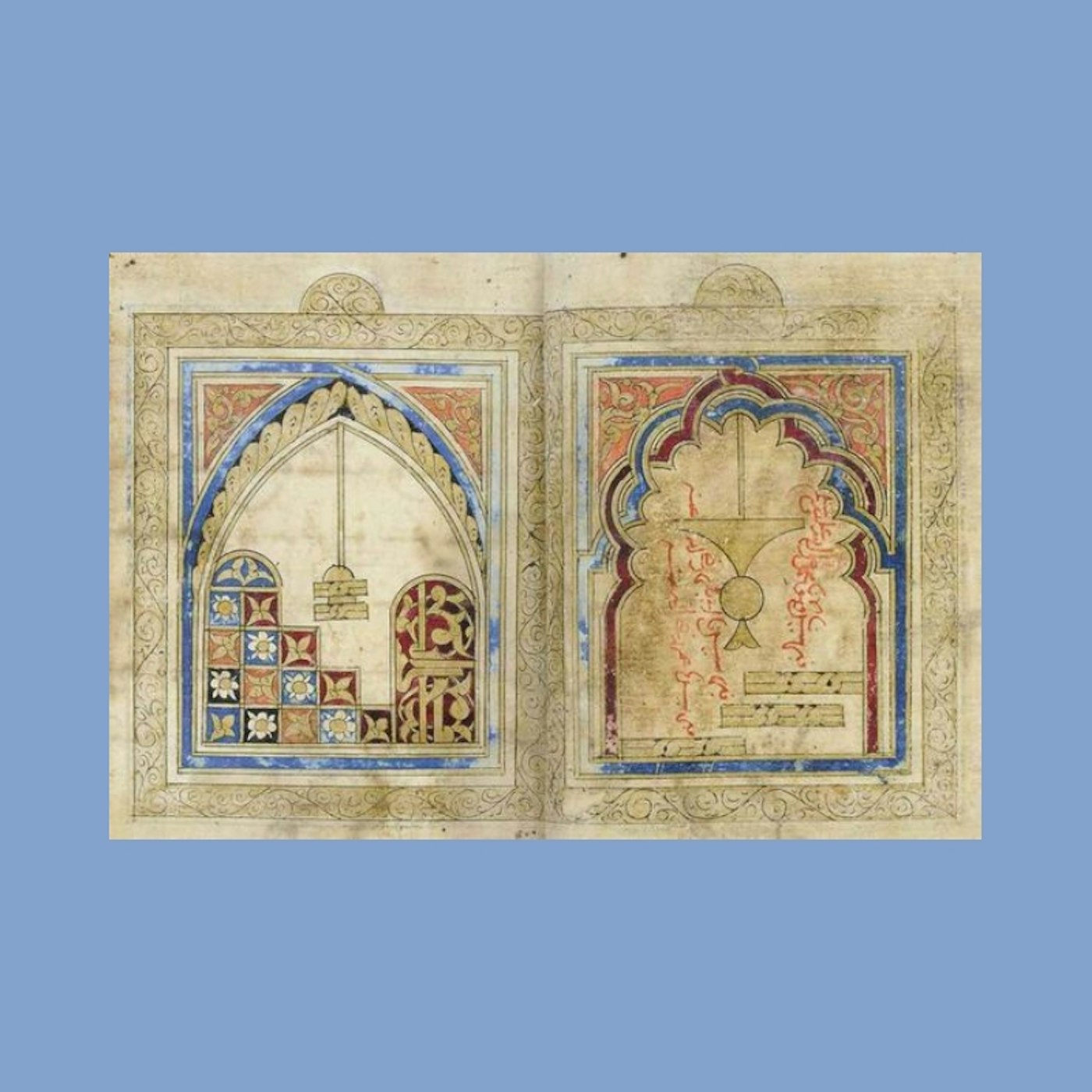

Feature Image: Christies.com

Bless the Prophet Muhammad, the Prophet of Mercy and the leader of the Ummah. Bless our father Adam and our mother Eve and bless with them their offspring: prophets, friends, martyrs and the best of us. We, the people of the heavens and earth, call for blessings for all of your angels and bless us with them, oh the most merciful of the merciful. (Muhammad Bin Sulayman al-Jazuli, Dala’il al-Khayrat, Cairo: Kashida Publishing House (2017), pg 57.)

In times of crisis, such as the times we find ourselves in now, Muslims commonly comfort each other by saying that we’re Muslims, that – alhamdulilah– we have the tools to weather anything. We tend to nod knowingly and move on but then in private exchanges, some of us admit that we don’t quite know what that means; at least, I don’t know what that means.

Are these tools a reference to how we feel about the Dunya and the day of judgment?

Is it because we’re told to rely on God?

Is it because we have the faith itself to comfort us and give us meaning?

But does everything work for everyone?

Maybe we don’t need to talk about how Islam comforts us, but how we can sustain that relationship with Islam and thus, what in Islam creates our belief in God.

One way of answering that question of ‘how’ is that Islam is aimed at building our spiritual muscles. Every act of devotion can develop character and must be done consistently in order to maintain its muscular definition within our souls. If we regularly remind ourselves of the importance of certain character traits, we can one day begin to embody them; partly because of repetition, partly because we repeatedly remind ourselves of the value of these aspects of character, and partly because we begin to seek out these characteristics in those we choose to have around us. It is in this mechanism that I take comfort, because it reminds me to work at everything I hope to be, but reminds me that I am only human and can’t be expected to embody everything now.

Right now, in the face of global uncertainty, I reach for humility to comfort myself. As a principle, humility takes me and throws me against the expanse of history, in the expanse of the Muslim cosmos; I am small and I will always be small. Then the pressure of having to achieve –encouraged by capitalism and individualism– begins to flake off; life becomes about having an impact only on the people around you. I was never designed to be more than part of the ummah: not an angel, not a prophet, but part of the greater Muslim universe. But meaning very little in the human expanse, in the Muslim expanse of the cosmos does not mean my relationship with God and his Prophet is any less personal.

“Bless the Prophet Muhammad with the light of guidance. Bless the one who directs people towards good, who calls them to guidance; he is the prophet of mercy and the one who stands before those with taqwa, and he –the messenger of god after whom there is no prophet– leads them. As he delivered your message, as he counseled your people, as he recited your verses, as he protected your bounds and what is owed to you, as he kept your covenant, as he performed your judgements, as he ordered obedience to you and as he forbade disobedience..…bless the Prophet Muhammad.” ( Ibid., 64.)

One little trick to remembering this principle that works for me is reading Dala’il al-Khayrat on a regular basis. Written in the 15th century by a member of the Shadhili tariqa, Shaykh al-Jazuli, the text is iconic and considered one of the most popular texts ever written in Arabic and in Muslim cultures more generally. The Dala’il is focused on the Prophet Muhammad –it is a selection of prayers for him– divided into 7 or 8 ahzab (depending on the edition). But each hizb, or section, contains a balance of themes. Central amongst them is the Prophet PBUH, true, but the Dala’il also includes a presentation of Muslim cosmology: how we are supposed to see our world as Muslims. It elegantly does so by incorporating dua’ in for different elements within Muslim society: the ahl al-Bayt, the other Prophets, and the ummah, never of course neglecting mention of the reader themselves and their individual needs. So although reading it is essentially an extended dua’, the reader is also reminded of the many different elements that make up our Muslim world and how important they are, all underscored by the importance of God and his Messenger PBUH. I affectionately call the Dala’il ‘the accordion book’, because it can do so much in such a small space –roughly a hundred pages–, as well because of its hizb structure, which allows the reader to read as much or as little as they want in the space of their day.

The Dala’il also plays with numbers. The slim text invokes the idea of infinity every couple of pages. You ask for prayers that number all of the breaths ever taken and that ever will be taken; all of the waves in the sea; all of the planets in the cosmos. The numbers themselves defy any human comprehension. It’s another level of realizing how small we are, but also how little we know. We don’t have the capacity to understand the vastness of life, and how many things make it up. Whatever we know is limited, both by our own capacity to store knowledge and our capacity to understand that knowledge. I can let go again and fall backwards into the sheer pleasure of having no control over anything really.

Bless the Prophet the number of drops of rain, the number of leaves on trees, the number of ships in the desert, the number ships in the sea. Ibid., 37.

But that line of thought –imagining how small we are and using the Dala’il to spark that thought within ourselves daily– might not work for everyone. It is completely OK to feel panic and fear; it does not mean one is not humbled by the expanse of the universe or that one is not humble to begin with. We have the example of a human Prophet PBUH, who grieved those he loved and felt fear, even when relying on God. And we have a faith whose intellectual history emphasizes pluralism, not only in difference of opinion, but in different approaches for different personalities who adhere to our faith. So there are other ways you can use Dala’il al-Khayrat. You also don’t have to use it, if something else works for you, like music or art that reminds you of all of the themes; Islam contains multitudes and is both one-size-fits-all and customizable at once. The Dala’il works for me, though, and I need to work harder at incorporating it into my own routines.

If you’d like to use Dala’il al-Khayrat, most editions in Arabic are fairly good; this one is visually stunning. I recommend this edition for English translation.

N.A. Mansour

N.A. Mansour is a historian and a PhD candidate at Princeton University’s Department of Near Eastern Studies, where she is writing a dissertation on the transition between manuscript and print in Arabic-contexts. She also produces podcasts for the Middle East Studies Channel on the New Books Network, for the Maydan and co-edits Hazine.info, an archives blog. She also writes for the general public on Islam, popular culture, and history.