The Mother Tongue as Resistance – Reflections on the Subtle Power of Our Native Languages

by Afroze Fatima Zaidi in Culture & Lifestyle on 22nd February, 2022

In July 2018, my dad passed away. He had never spoken much, but so many of his words are forever etched in my brain. “Roti dastarkhaan pe aakhir mein aani chahiye” he would say, “The bread should be brought to the table last,” out of respect for bread. “Hum nana hain”, he said, “I’m his grandfather,” when my son, aged 18 months, broke a glass side table and I offered to replace it. “Yaadein toh saathh le ke ja rahay hain,” he said, “We’re taking the memories with us,” after a picnic when my cousin joked about leaving memories behind when we were heading home.

I remember his voice. His words, always clear and well-enunciated. His tone, always calm, slightly lyrical, almost soothing even without intentionally meaning for it to be so. His volume always low, even when something annoyed him. Always full of love. And always in Urdu.

Even though we didn’t grow up in Pakistan, we grew up speaking Urdu. We were in Dubai, a city which, even in the 80s and 90s, very much had English as the lingua franca. I have spoken English ever since I was able to talk. I did a Bachelor’s degree in English. I make a living writing and editing English. As a mother now living in the UK, I speak English with my children. But few things have made me realise my connection to Urdu more than my dad’s passing.

Afroze’s Father

We called him Pappa. Not Puh-pah as in the French, or even Paa-paa in the common subcontinent way. But Pup-pa – incidentally also Urdu for ‘big kiss’. Which sounds funny enough but is made funnier still when considering how unassuming he was as a person. It’s not that Pappa didn’t speak English. He had worked in a bank for thirty-five years. Growing up, we had an English newspaper delivered every day, of which he was the main and often only reader. And we had a subscription to National Geographic for years. So despite what his Pakistani accent might have suggested, Pappa wasn’t just conversant in English, but completely literate.

And yet, because such is the fragility that comes from a brain affected by both Parkinson’s disease and dementia, in his final years his English skills began to deteriorate. At the same time, he lost his sight to glaucoma and much of his hearing and sense of taste to old age. A few years before his death, at an assessment for dementia which I attended with him, the doctor asked him what he remembered of his childhood. Throughout that appointment, I kept feeling like maybe he was struggling more to answer the doctor’s questions because of having to respond in English.

When asked about his childhood, Pappa said he couldn’t remember anything. He was seventy at the time – old, but not old enough to have no childhood memories at all. I remember watching him in that moment. He was frail, his expression a little lost because of the glaucoma, but so dignified. I remember feeling a profound sense of regret at not talking to him more about what his childhood was like. I remember feeling heartbroken and helpless, and being glad that he couldn’t see my eyes well up in the doctor’s office. I remember being overwhelmed with sadness at the thought that those stories, that piece of his history, and mine by extension, was lost forever.

Afroze and her Father

Over the coming years, Pappa’s health continued to deteriorate. When he finally went into hospital for what we thought was an ordinary infection, we didn’t know he would never come back home. While he was there, we tried to visit him every day. There was no TV or radio in his room and he couldn’t see well enough to read. He would say his daily prayers sat up in his bed and recite his dhikr on his plastic turquoise-coloured tasbih. It was all he could do to pass the time. He was never much of a talker, but particularly with his English skills deteriorating, chatting with the staff was out of the question. Staying in the hospital made him lonely and restless, and even though he never said it, I knew he looked forward to our visits. So one day, while we visited him – my mum, sister, the kids and I – I decided to ask him about his childhood. I still remembered the day he had his assessment for dementia, and I was desperate to know him more while we had the chance.

I asked him what he was like in school. He said the other kids would copy his work, but the teacher would check his work last and tell him off for copying from them. “Wouldn’t you tell the teacher they copied from you?” “No, I wouldn’t,” he said, making light of it. I asked him about when his family moved to Pakistan from India. To what city? With whom did they stay? How old was he at the time? The memories that were lost to him in English flowed forth with ease in Urdu. As I asked, my sister started recording on her phone. We didn’t know it would be the last time we would record him speaking to us. Our sweet Pappa, with his turquoise-coloured tasbih wrapped around his gentle hand. With his lyrical tone and kind nature and perfect Urdu. The Pappa who didn’t get his classmates into trouble, even if it meant getting blamed for something he didn’t do. The Pappa who raised us with lessons of faith and fairness and justice and knowledge and independence. And ingrained in us so deeply a sense of who we are and where we come from.

Probably because of his introverted nature, he was never actively political. Yet he definitely knew and understood politics, and he was committed to justice. And despite us never seeing either of our parents ‘be political’, I understand now how as parents, they taught us resistance. They immersed us in a culture that was part of us even though we didn’t always feel part of it. They kept us tied to a sense of identity with which we could connect to the past while also being able to know ourselves in the present. Not out of any sense of ethno-national pride, but merely because they passed on to us the norms and customs that were familiar to them. It was effortless in its simplicity. And yet immensely powerful.

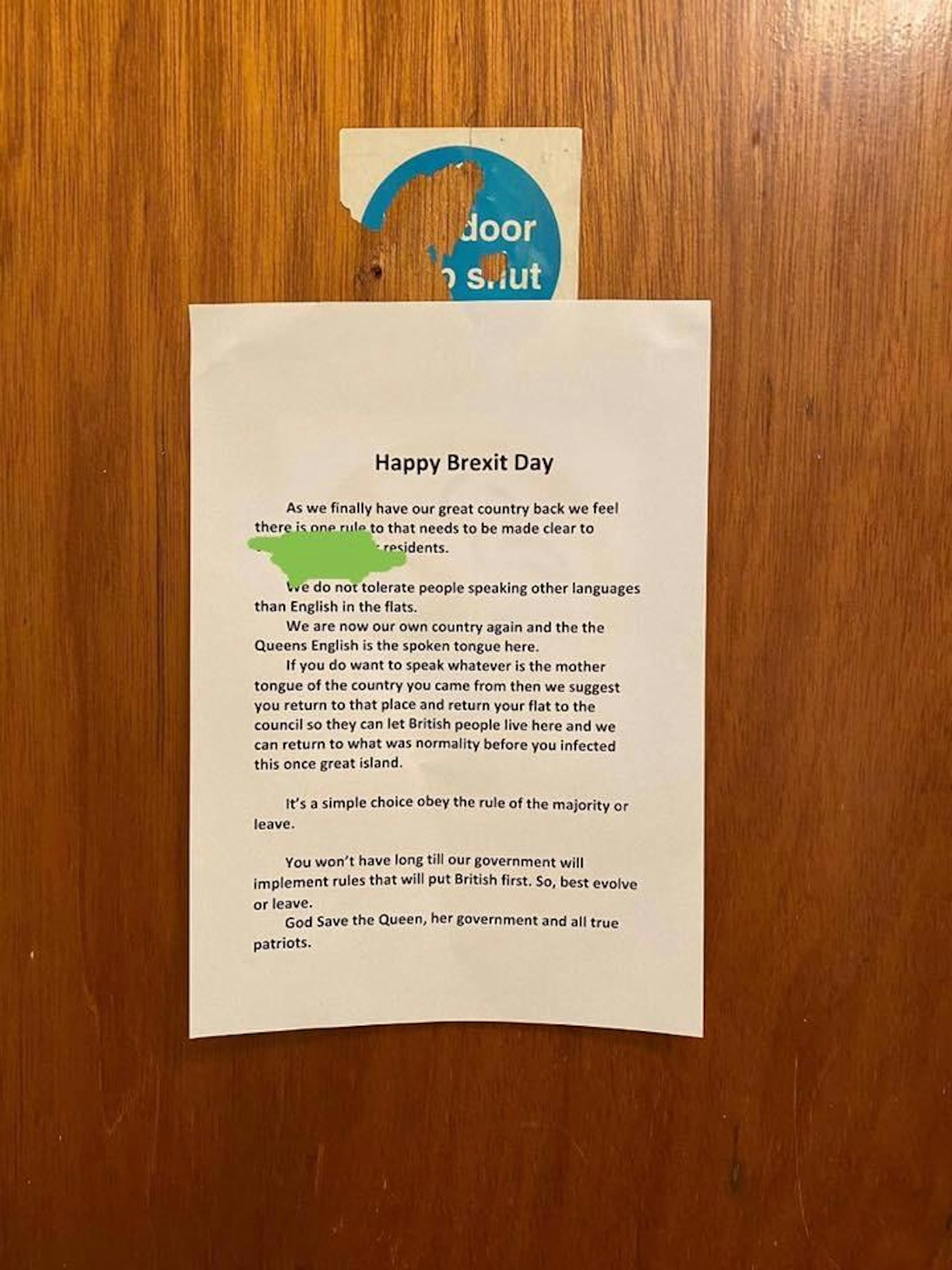

After my dad passed away, and particularly while living in Brexit Britain, I have come to appreciate like I never did before the significance of this connection to our culture. The ability to know it and express it, comfortably and confidently. The need to cherish, preserve and pass on as many elements of it as we possibly can to our children. The courage to speak the language of our ancestors, even in the face of obvious hostility.

And language is particularly significant because so much of our lived experience is tied to it. So many everyday turns of phrase defy translation. So many expressions of creativity in the form of song lyrics and poetry and popular culture. Along with a diverse array of inflexions and intonations that reflect the heritage particular to us. Language is the vessel that contains our interactions with people and culture and, by extension, life itself. It is our ability to interpret and make sense of the external world as well as our own internal thoughts and feelings. It is the web that connects us and binds us together as human beings. Not just interpersonally, but across space and time, through literature and poetry, folk tales and oral history.

So when ethno-nationalists get angry at people for speaking another language, this is why. It is immediately threatening to them as an expression of our identity that makes us unassimilable, uncolonisable. It is our secret handshake. Our secure line of communication. Our exclusive, members-only club to which racist white folk will never gain access. I think somewhere, maybe subconsciously, as first-generation immigrants my parents knew they were sending us into a world that would make us conform to its norms and values. Wear their clothes. Consume its fast food and entertainment. Speak its language. So they made us hang on to what was ours. They made us resist – conformity, assimilation, colonisation.

Want to listen to Afroze Fatima Zaidi read this beautiful piece herself?

We thought it was about time that we turn some of our most read pieces over on Amaliah.com into some of our most listened to tracks on the Amaliah podcast. We present to you the Amaliah Anthology!

We’re bringing amaliah.com articles to life with readings by the authors themselves, so that you can enjoy your favourite pieces in a new way.

Click to listen to Afroze Fatima Zaidi reading her piece below, and click here to listen to the rest of our Amaliah Anthology series now…

Afroze Fatima Zaidi

Afroze Fatima Zaidi is a writer, editor and journalist. She has a background in academia and writing for online platforms. She tweets at @afrozefz