Non-Patriarchal Readings and Male Ownership of the Quran; an Afternoon With Asma Barlas

by Tahmina Begum in Culture & Lifestyle on 17th January, 2019

Amaliah are not in partnership with New Horizons and do not endorse them. The views of our contributors in articles do not reflect those of Amaliah.

My immediate reaction to finding a book translating the Qur’an from a non-patriarchal reading nor feminist one (in Barlas’s words, feminism is usually a colonialist act of largely trying to tell Muslim women they’re oppressed) was FINALLY. Yet a thought that closely followed was why have I just found out about this?

Barlas first wrote Believing Women In Islam in 1999, after her experience as the first woman to be inducted into the foreign service in Pakistan in 1976. She was later dismissed by General Zia ul Haq on the same day she left her husband – her in-laws worked closely with the general and twisted a diary entry by Barlas, so the now academic and lecturer at Ithaca College, had to seek refuge elsewhere.

The title covers everything that is usually misconstrued about the treatment of Muslim women from both in and out of the ummah. For example, the book looks at what the Quran says about how women should approach divorce, women initiating sex and how husbands should argue with their wives and when they should seek counsel from a non-patriarchal reading nor lens.

Asma Barlas’ Believing Women In Islam has now an introductory edition assisted by David Raeburn Finn as in Barlas’ words, ‘[it’s another example of] trying to get the academy to the community’ she says. So it makes sense that as part of her UK tour meant an intimate three hour round table talk hosted by platform New Horizons in British Islam, discussing the Qur’anic text from a non-patriarchal view.

Instead of an entire breakdown of Believing Women In Islam (please buy it, it’s literally changed my life), here are the key learnings I took from the session and of Believing Women In Islam.

At the beginning of the round table discussion, Barlas asked the nine of us in the room to shout out things we’d heard about women and the places we’re supposed to occupy according to the Qur’an. Some of us proclaimed with our chests, “women are not supposed to lead the household” while others talked about those heavenly seventy virgins promised to men. Yet the central thread in Barlas’ teachings that day and across her titles is this removal of the idea that the Qur’an can only be understood and interpreted by an elite group of men.

Amaliah is not in partnership with New Horizons and do not endorse them. The article is not a reflection of the views of Amaliah but the author’s experiences.

General pointers on how to read the Qur’an as advised via Believing Women In Islam

The Qur’an counsels for the text to be read as a whole not to be taken apart

The Qur’an criticises those who ignore what is clear instruction when there isn’t any symbolism or metaphorical lines

A reminder that Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) was a supporter of women’s rights and was known for seeking women’s counsel for issues.

- On religion becoming about identity, not God

When asking Asma Barlas why our ummah cared so much about the ‘big sins’ i.e. not drinking, eating pork, withstanding from sex before marriage, women covering their bodies instead of the other teachings in Islam, Barlas stated, ‘religion has become about identity and not about God’. So much of the time, we are trying to shape the Qur’an to our lives instead of the other way round, with text from elsewhere. Whether that’s op-eds about women’s rights and Islam or even when we’re trying to question how ‘halal’ a situation is. But as it’s been said many times before, it’s all here, it’s all in the Qur’an. Barlas has simply made it available for everyone to read it and see it from a less dogmatic perspective.

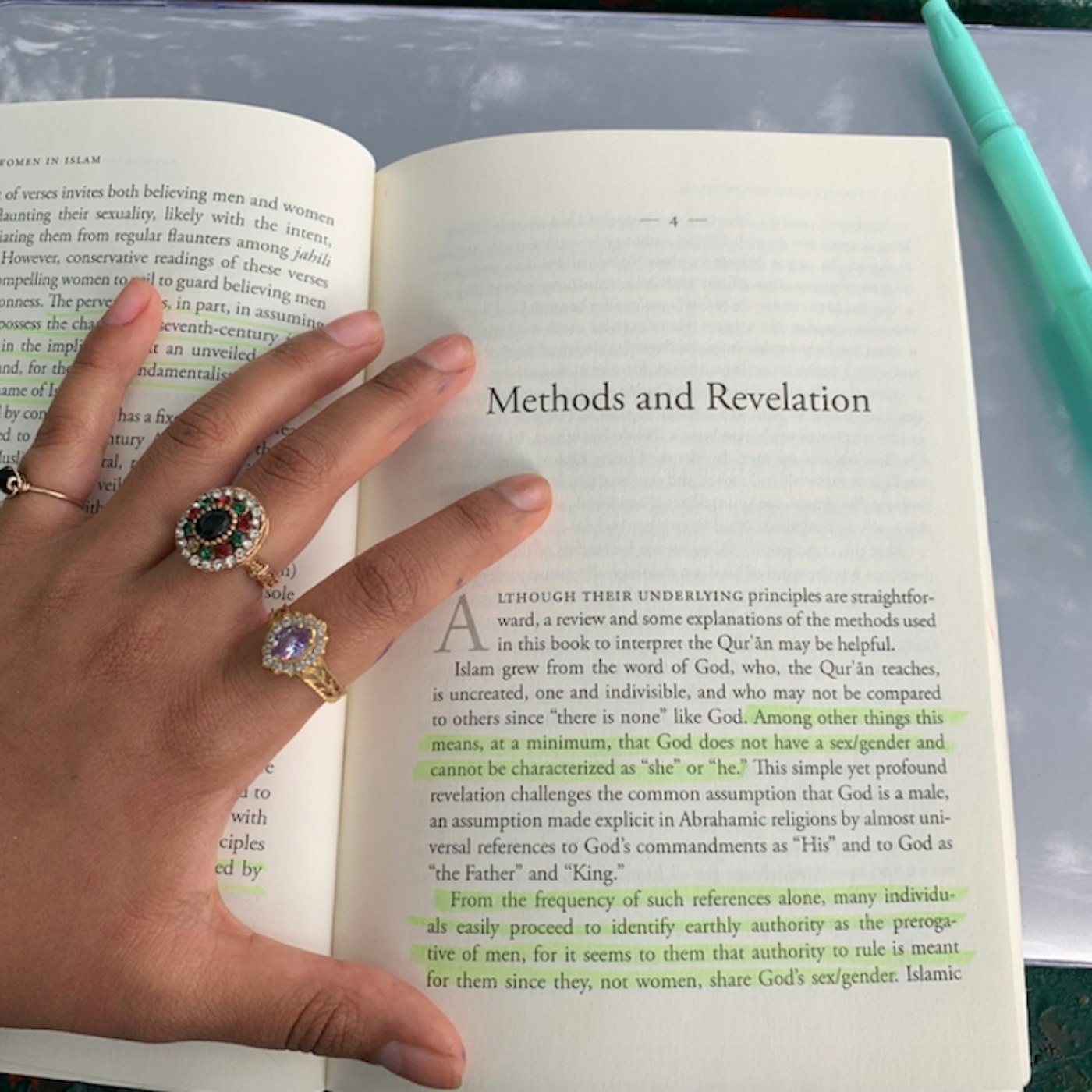

- On God and gender; he, she or they

As Believing Women In Islam is a non-patriarchal reading, the first foundation Barlas lays is that Allah has no gender. To say that the Qur’an can only be interpreted properly by men or that men have a higher presence both in Islam and humanity is to lift men to God’s standards and lower Allah to man-made male attributes. As Barlas says “Divine authority is neither male, nor is it shared”.

The Qur’an doesn’t define nor limit what it means to make a ‘man’ or ‘woman’

What has usually been passed down through conservative Sunni readings of the Qur’an is the appraisal of women being passive or simply quiet in order to uphold morale when in fact, Barlas argues this is usually to uphold men’s honour – something that is burdened on the shoulder’s of women. “In brief, the Qur’an does not say by virtue of being biological males, are intelligent, rationale, and moral and that women, by virtue of being biologically female, are unintelligent, irrational and immoral,” says Barlas.

It could be ‘She’

Sometimes when reading the Qur’an, one may ask why it’s always He. He who is merciful. He who is all-knowing. When actually Barlas points out that He is just the formation of the Arabic language. It could easily have been She or Them.

- We can’t think about the Qur’an contextually

“Would God, all-knowing and wholly compassionate, frame a message to future generations of men and women who remedies were limited to misogynistic practices of seventh-century Arabia?” is a question Dr Barlas probes at the beginning of the round-table discussion but also in her third edition.

For many of us who try to debunk the patriarchal myths about how women should be in the Qur’an, a common excuse is “we have to think about when the Qur’an was written and the people of that time” when actually Barlas states the Qur’an was not just merely sent down for the jahili society.

Barlas practises that God did not ignore humanity’s imperfections, therefore, was “the Word not also meant to remedy misogynistic injustices of future centuries?” A just and compassionate God would not fail to notice the differences in physical strength, the different trials, if anything, he created the differences for a reason.

So when we remove the patriarchal lens that men should lead the religion (as the Qur’an has been transcribed and interpreted largely solely by men, usually for some kind of political gain or status-furthering agenda), Barlas concludes by following what the Qur’an advises: if you have any questions, look here.

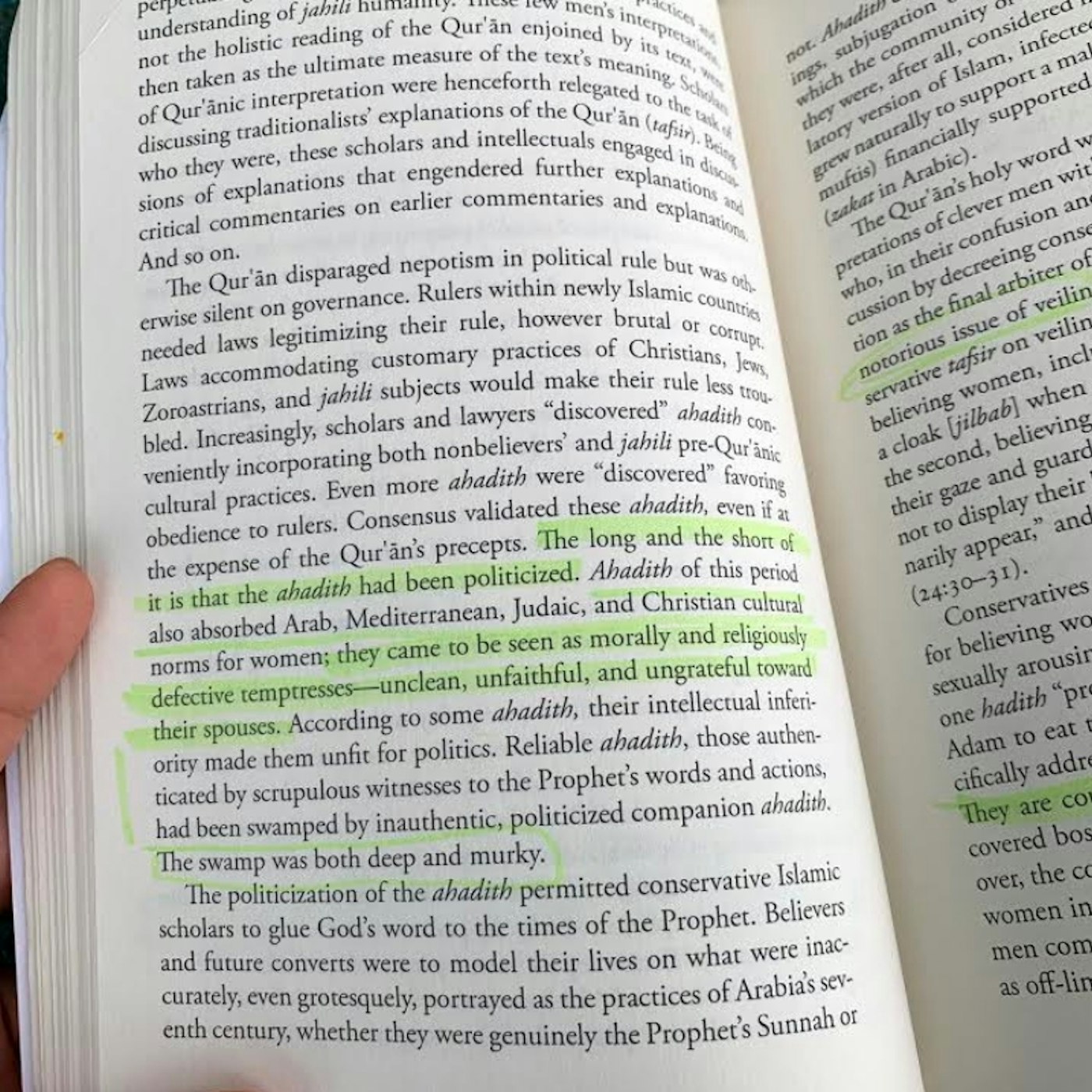

- On verifying your hadiths

“Who authored the hadith in question?” asks Barlas. “If the author lived well after the Prophet’s death, could the hadith nonetheless be traced to a companion? Did the hadith contradict the Quran?”

Though Barlas personally does not follow hadiths as stated in Believing Women In Islam, questioning the source of hadiths is one I had not really considered even when recognising that interpretation is personal as well as political. Yet Barlas in this chapter argues that she doesn’t follow the hadith on grounds that many tellings of the Prophet (PBUH) and his ways of life have risen to the surface hundreds of years after his life and tend to be patriarchal in its teachings but treated as sacredly as the Qur’an; when in fact hadith’s are not mandatory to follow.

- On male ownership and the Qur’an

The issue with patriarchal readings of the Qur’an is that many followers of Islam, including both men and women, believe because of the line “men are maintainers of the women with what God bestowed on some of them over others and with what they spent of their money,” this may translate to men being autonomous over both sexes. When in fact, it’s important to remember Barlas says, that the Qur’an was revealed in the time of the jahiliyah, where men had hundreds of wives and would discard them with no care.

The argument here with finance is that when men spend their money on their families, they are maintaining their families including their wives. The issue with a patriarchal interpretation of this sentence is that being a ‘maintainer’ has validated some husband’s entire control over their wive’s life. Male ownership may also manifest in the differences in the types of career paths men and women pursue, who ‘leads’ the household, whose voice is listened to and adhered to and simply, whose choices are put first and matter.

But in today’s society, women are not discouraged to earn and look after their families in a financial sense too. Nowhere does it say, women or a wife cannot also be maintainers in the Qur’an.

- What men are told about consent in the Qur’an

The myth that men are to lead in Islam can sometimes translate to in real life, men owning women’s bodies. When in fact all passages instruct men on how to approach their wives in the bedroom.

“So leave women alone at such times and do not seek their intimacy until they bathe” is an example of a husband being told to leave his wife alone during menstruation and the idea of ‘seeking’ a wife’s intimacy is a reflection of the consent required in the first place.

- The infamous beating a wife ayah

Not only do Muslims believe that we, humans, were made in pairs but that Qur’anic rules of marriage say that partners must fulfil love between partners through care for one another but also have mercy on each other.

The line ‘Lastly, beat them (lightly)’ when conversing about men being protectors is translated in the era of Modern Arabic: a time after the Qur’an was revealed. For many translations, this beat is actually to tap a wife for her attention when in a situation where the Qur’an describes a dispute where anger, emotions and upset is in the air. The tap is a metaphorical way of saying ‘look past your anger’ i.e. ‘wake up’.

When reading this chapter about how husbands and wives should argue with each other, this tap is, in fact, a part of a larger reading about patience, guidance and seeking outside counsel if there is trouble in the marriage that can not be consoled between each other. However, the word ‘beat’ which has been arguably inserted through the language of Modern Arabic is yet focused on and used to validify abuse. During this session with Dr Barlas, the scholar made a great point: ‘Even if the text advised you to hit your wife, why would you want to do that?’

—

Growing up in a Sunni household where hadiths are revered and patriarchal traditions can be upheld, it was freeing to read Believing Women In Islam where Dr Asma Barlas takes apart misogynist interpretations and interprets the Quran simply and as a whole.

What’s also a liberating read is that she also does not use the label nor the framework of Western feminism. Believing Women In Islam does not read at all biased.

A book that is now full of annotations, highlighted passages and notes, I did exactly what Dr Asma Barlas told us she set out to do: “I didn’t write this so women could agree with me, if anything, I wrote this so women, men, everyone could see that there isn’t one way of looking at something that is actually advised to be discussed, but is instead trapped in being taught through a narrow lens that benefits only one group of people. I just hope that women everywhere could make their own minds up about the Qur’an and their religion, not just what’s told to them’. Thank you Dr Barlas, I’m doing exactly that right now.

Tahmina Begum

Tahmina Begum is based between London and Birmingham and lives by the hashtag #badandbengali. Working as an editor and journalist for the past 8 years and with recent bylines in I-D, Dazed, AnOther, HuffPost UK, Metro and more, Begum is also CEO and EIC of the print publication and platform XXY Magazine. She has recently contributed to Comfort Zones, a collection of essays in aid of Women For Women UK, writing about second-generation guilt and ease. Her work focuses on culture, communities and connection. IG: @tahminaxbegum