Wearing a Hijab for a Few Hours Will Not Eradicate Islamophobia, We Need to Confront White Supremacy

by Shereen Fernandez and Fatima Rajina in World on 22nd March, 2019

We watched in horror as the news unfolded last Friday that two mosques had been stormed, our bodies treated as targets because they were seen as Muslim and embodying Islam, considered to be ‘out of place’. After 51 Muslims were massacred before Jummah salaah in New Zealand, some have been searching for a glimmer of hope that everything will be ok. For Muslims especially, this has been a painful and traumatic time as we reflect on how familiar those spaces of worship are. These white supremacist attacks are happening anywhere and everywhere; white supremacy knows no boundaries and penetrates our everyday spaces. Living in London, we must also admit that this profound shock stems from the fact that an attack like this happened within a ‘developed’ Western nation again so familiar to us.

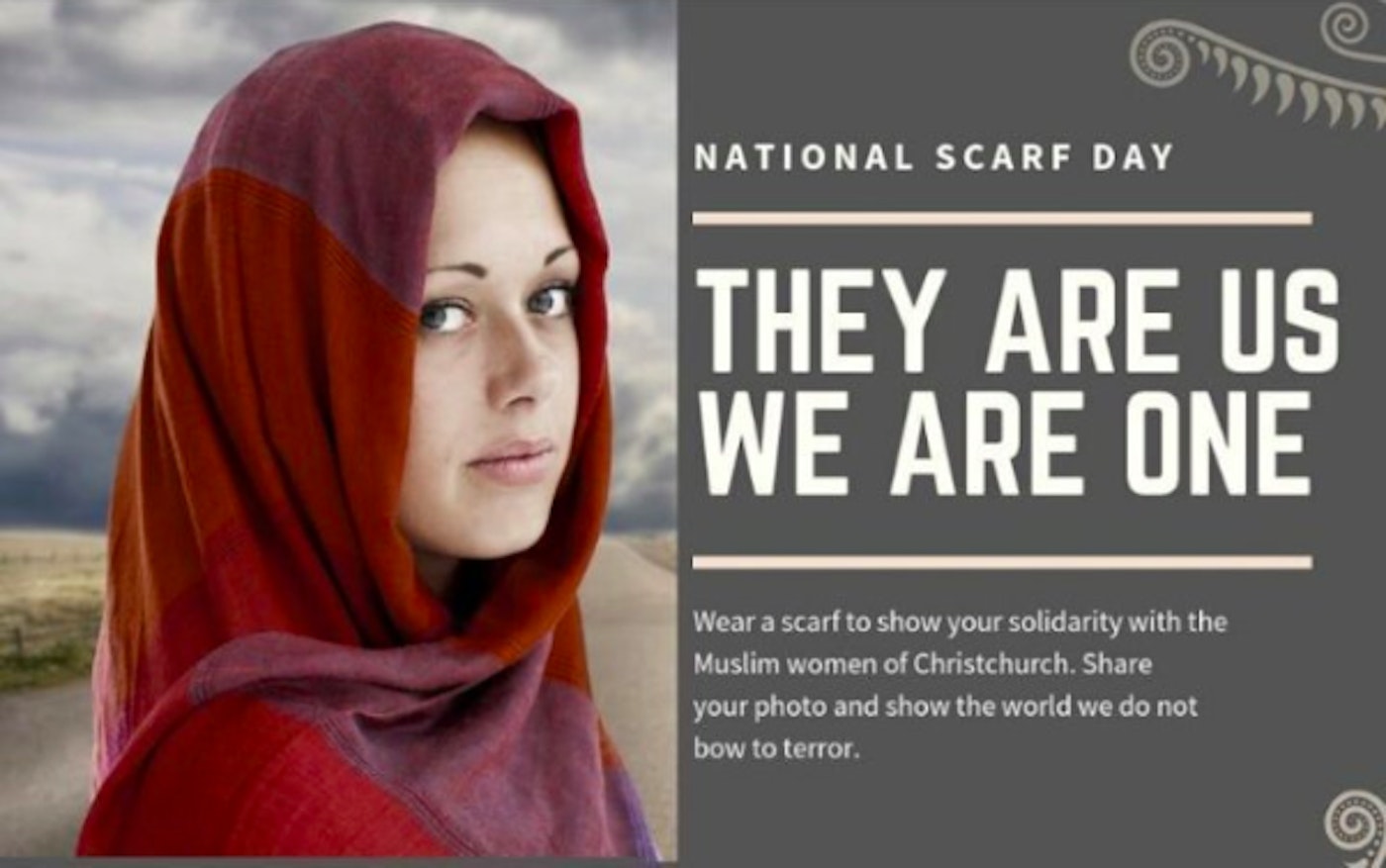

In a search for hope, a campaign was launched which asked non-Muslims to wear the hijab for a day in New Zealand, to mark the week anniversary of the attacks. The campaign was organised by a group known as ‘Scarves in Solidarity’ and their promotional poster reads: ‘Wear a scarf to show your solidarity with the Muslim women of Christchurch. Share your photo and show the world we do not bow to terror’. The picture on the poster is of a white woman wearing the hijab loosely, standing in close proximity to the words, ‘They are us, We are one’. But are we? And for how long? Who were we before we were incorporated into the ‘us’?

These campaigns must be understood as tokenistic gestures designed to erase the very histories that led to these deaths.

Rather than confronting the logic of white supremacy and the normativity of whiteness, the campaign tries to make us ‘one’ whilst doing nothing to challenge the structural discrimination that persists. Others have already argued that the Twitter #TheyAreUs trend sanitises the image of New Zealand, yet relies on the same old ‘colonial governance’ which racially categorised people into “‘they’ (the barbarian) and ‘us’ (the fully civilised human)”. In the search for hope, some Muslims across social media have applauded this campaign because of the ‘kind gesture’ of solidarity it extends, but we must question the temporary nature of this gesture; at the end of the day, once the hijabs come off, what are we expecting to happen? How would this help to challenge the structural inequalities and vicious Islamophobic language in the mainstream media that has led to this and many other attacks? We must ask: when we focus on superficial gestures of ‘togetherness’, have we set the bar too low?

Hijab day campaigns are not just limited to atrocities like New Zealand but also emerge during Islamophobia Awareness Month campaigns to give non-Muslims (in particular) the ‘experience’ of being a hijabi. This perpetuates stereotypical images of what it means to be a Muslim woman, reducing our experiences and identities to the fabric on our heads that one can slip into to show ‘solidarity’ if and when they choose to.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Samantha Hayes (@samanthahayes) on

This is a privilege that visible Muslimahs cannot afford and we must reject attempts at humanising Muslims just to make others feel comfortable and guilt-free. When putting on the scarf for a day, these non-Muslim women end up centering themselves; the only way the lives and trauma of the Muslim ‘Other’ can be understood and grieved is through erasing all of our differences. Rather than engaging in tokenistic expressions of solidarity, we must ask our non-Muslim counterparts if they are willing to do the necessary work to tackle a culture of Islamophobia.

don’t have the breathe to waste but guys WE DONT NEED RANDOM WHITE WOMEN TO WEAR HIJAB FOR A DAY THERE IS A CULTURE OF MASSACRE THAT THEY’RE DISTANCING THEMSELVES FROM HAVING TO DIVEST FROM BY DONNING A CLOTH FOR A DAY – DEAL WITH UR RACISM smh I WILL NOT CELEBRATE THIS 🗑🗑🗑

— Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan (@thebrownhijabi) March 20, 2019

At this very moment, we need fixed and focused anti-racist campaigning which calls out the terror of white supremacy and acknowledges the histories of exploitation and racism faced by communities of colour.

New Zealand, as a settler-colonial state, must urgently address its past violence, especially against the Māori community. As Asim Qureshi says: “Ultimately, if New Zealand hopes to have any chance of recovery from what it has suffered, then it must first seriously confront its own colonial history, and how that colonial violence continues to be excluded from the foundational myths of New Zealand as a tolerant society.”.

The struggles faced by communities of colour are not isolated but rather, are part of entangled histories. We settle for too little when we are happy with these ‘wear a hijab for the day’ campaigns. It is relatively simple to wear a hijab for a few hours and ‘perform’ solidarity but what is really required is to transform and heal a broken society by confronting our biases and our complicity in these systems of destruction.

This is easily avoided when we fall back on ‘gestures’ which allow non-Muslims to say that they’ve done “the work” for a day (and nothing else). The praise Jacinda Ardern has received for donning a dupatta whilst appearing in a masjid is an extension of this, as we refuse to confront the harassment hijabi and niqabi Muslimahs face daily. We must ask if we’ve set the bar too low when even Muslims are fawning over the Prime Minister whilst our murdered community are slowly disappearing from focus.

Even as some argue that in light of the abysmal leadership in the UK, USA, Australia, etc. Arden is showing ‘proper’ empathy, yet should we really be this grateful for a head of state that is doing her job (even when she is doing it empathetically)? The very people who are violently racialised day in, day out are no longer the focus or the priority.

The attacks on Friday revealed the urgency of confronting white supremacy and although People of Colour, in particular, Black Feminists, have been warning us about its dangers, their warnings were ignored. You do not need to wear a hijab to ‘feel’ Islamophobia or to feel sympathy. Instead, sit back and listen to the accounts of Muslims who can tell you their reality. Think about the spaces you occupy and question what and who is missing.

In times of catastrophe, we urge you to read beyond the headlines and hashtags and make sure that the legacy of those who died is not cheapened by superficial acts of solidarity. The real work starts now.

This article was written by both Shereen Fernandez & Fatima Rajina

Shereen Fernandez is a PhD researcher at Queen Mary University. Her research looks at the implications of the Prevent Duty and fundamental British values on schools, teachers and Muslim communities in London. Her research looks at questions around securitisation, belonging, everyday ‘Muslimness’ and visibility.

Twitter: @shereenfdz

Fatima Rajina joined Kingston University as a Lecturer in Sociology in 2018 and currently teachers the UG courses ‘How to Change the World’ and ‘Researching Race and Ethnicity.’ Completing her PhD at SOAS, University of London, Fatima’s work looks at British Bangladeshi Muslims and their changing identifications and perceptions of dress and language. She is currently working on a project, Lutonians, along with a local photographer, Ahqib Hussain, to document the everyday lived-experiences of people from Luton. She has also worked as a Research Assistant at the Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge looking at police and counter-terrorism. Fatima was recently a Teaching Fellow at SOAS.

Twitter: @FBRajina

Shereen Fernandez and Fatima Rajina

Written By Shereen Fernandez Fatima Rajina (See above for biographical Information)