“I Don’t Believe I Have Ever Heard Any Non-Arabic Person Pronounce My Name Correctly” – Book Review: The Good Immigrant

by Ilham Essalih in Culture & Lifestyle on 9th May, 2018

“For people of colour, race is everything we do. Because the universal experience is white.”

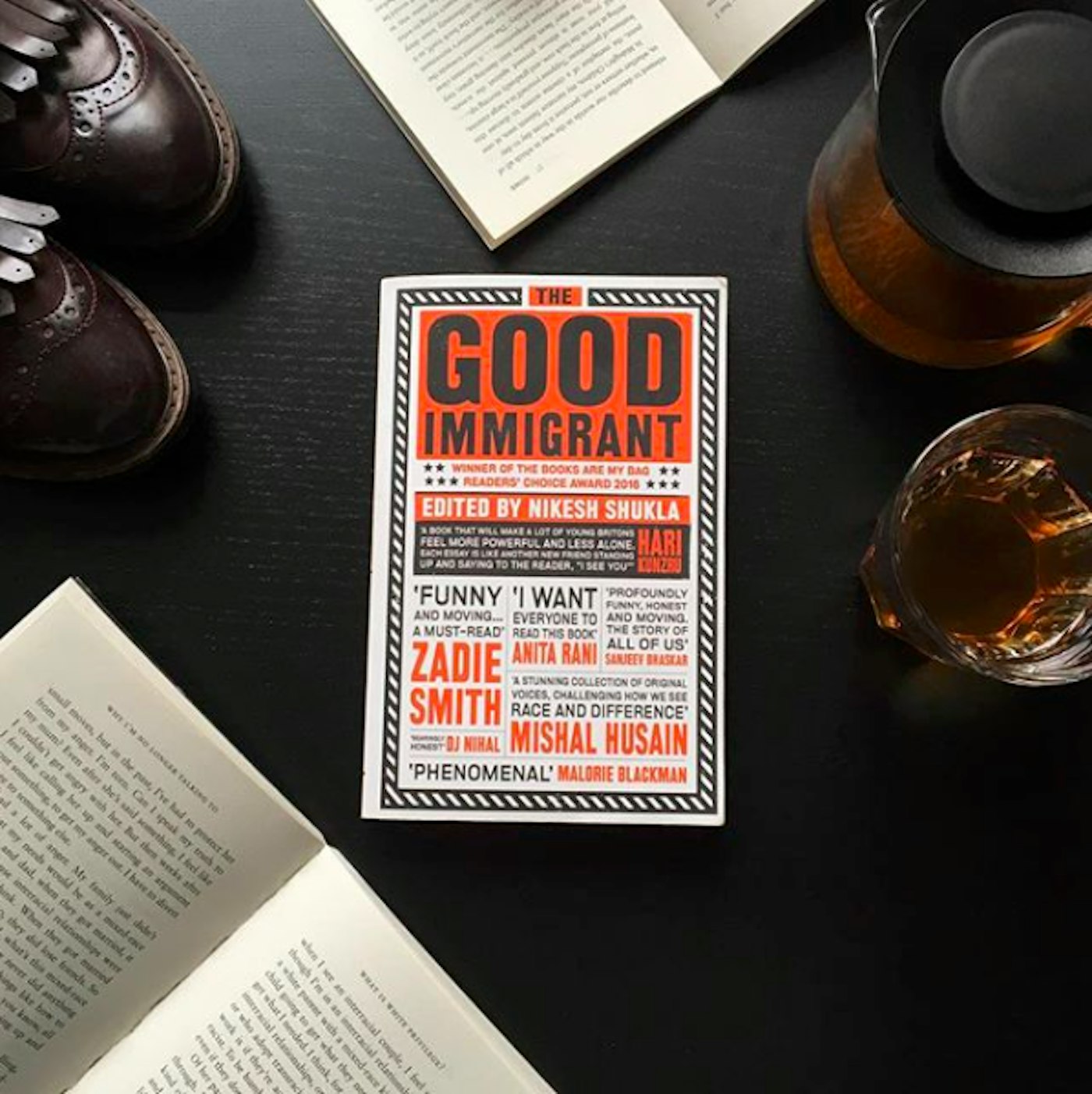

I got terribly excited when I read this line in the editor’s note of The Good Immigrant, because I couldn’t agree with it more and I was thrilled someone managed to phrase it this eloquently. The book, published in 2016, is a collection of essays written by British authors, artists and actors of colour. This book has been so celebrated and raved about and if you haven’t heard of it yet, you must have been living under a rock. There is great plurality in this book; the essays are all unique and different, and some might open your eyes on aspects of discrimination you’d never consider. Overall the book is easy to read, accessible and honest, it has no room for false pretense or ambiguity.

Back to the quote. It’s on the very first page of the book and it definitely sets the tone for the whole read. I believe the line rightly expresses the way many children of immigrants and non-whites feel in their daily life. This book is a blessing we were all waiting for; it contains stories we can relate to, voices and faces we can actually identify with. There is a plurality of experiences to be discovered, and you can choose to read the entire book in one go or flicker through the individual parts at your own pace and it won’t make the experience any less intense.

I am often told I am obsessed with race, that I see everything from my ‘racial activism glasses’.

I never attempt very hard to deny this, because it’s probably true and I am rather unapologetic about it. My experiences with racism and living in a fairly islamophobic society have conditioned me to think of race and its impact on my life on a daily basis, and have perhaps lead me to develop this ‘obsession’.

Most of the time, immigrants or their children carry the responsibility and burden of making themselves and their culture accessible and ‘pliable’ for whites. There is no ‘meeting the other halfway’, it is expected from us to integrate and most of the time also forgo our identities. In My Name is my Name, Chimene Suleyman mentions, “there is a whiteness that exists to be so tone-deaf it cannot make out our words, our gods, (…) nor our names” (30). I don’t believe I have ever heard any non-Arabic person pronounce my name correctly, and for the longest time I was convinced it was normal, and because it was foreign, it was up to me to offer people an ‘alternative’, a different pronunciation they could deal with. I tried very hard to make my name sound as white as possible, trying desperately to smooth out its beautiful Arabic tonality.

I often found myself damning the fact that I didn’t have a cute nickname that would make my life easier – or whiter.

Because as mentioned in Bim Adewunmi’s chapter, “the universal, is white” and “Whiteness – or, you know, white people – exists as the basic template.” (209) In Himesh Patel’s contribution to the book, the chapter Window of Opportunity, he writes, “Looking back, this dismissal of my Indian cultural reference points must have caused me to start burying that side of my identity – if it wasn’t relevant to my social growth, what use was it?” (65) My Arab-African identity was never useful for my ‘native’ peers, so naturally – and unfortunately – I tried very hard to deny it as a child and as a teenager.

The chapter that in my opinion is the most powerful is the final one, The Ungrateful Country by Musa Okwonga. They left the very best for last, trust me. It was also the one I could relate to the most, I highlighted so much of it that at some point I gave up on marking the best parts, because truthfully, they all were. In the opening lines, Okwonga describes growing up in Britain, “it was always a case of making sure that I was grateful” (224). Whether you’re in Britain or anywhere else in the world (read: the West), chances are you can probably relate to this as an immigrant.

I was born and raised in Belgium where my parents have been living since they left North Africa. To work for better lives, to get away from the poverty and misery of their small towns. My family always felt a sense of gratitude towards their ‘new country’, because they had been given a chance to come here and lead better lives than back home. Their generation was the one that kept quiet, that accepted injustice because ‘this was not their country’.

My generation was different, we were born here, this was as much our home as our fellow white peers’. Or so we tried to convince ourselves. We were never considered truly European, in fact, we have in the northern half of Belgium a commonly used word for people born here but who aren’t white; ‘allochtones’. This word comes from the Greek words ἄλλος [allos] other and χθών [chthōn] soil/earth/land, literally meaning ‘emerging from another soil’, while whites are known as ‘autochtones’, meaning ‘emerging from this soil’. This is an actual thing, and there is an undeniable racist connotation to the word, because the term allochtone would never be used to describe someone French, Spanish or Danish. It is only used for children whose parents are from Morocco, Turkey or Congo, aka the ‘less desirable immigrants’.

Turks and North Africans mostly came to Belgium after the European wars as ‘guest workers’ to rebuild the country, and most of them stayed when their work was done, and they had children and grandchildren here. In The Ungrateful Country, Okwonga phrases the sentiment perfectly; “It was as if, even though we had been born here, we were still seen as guests, our social acceptance only conditional upon our very best behaviour. I began to have less tolerance for this infantilising outlook, particularly when I looked at how much of the capital’s, and indeed the country’s, lowest-paid work was being done by immigrants with very little complaint. If there was anyone ungrateful about their presence in the country, it wasn’t them, it was Britain.” (231) It was also Belgium.

As a person of colour, it is always difficult fitting into society because of the perceived stereotypes and blatant racism, so you can imagine being a woman as well as a Muslim wearing a headscarf here. Many of my hijabi peers are unable to find jobs that match their degrees – sometimes it is even impossible finding work at all. One day, these countries will regret rejecting us, because at some point we will all have left and this soil will be left with nothing. Many of us are contemplating or have already decided to leave for a country more tolerant, a country that accepts us and actually embraces our differences. Like Okwonga, “I had grown tired of spending my time fighting those battles in the country of my birth.” (233) At some point, we just want to live normal lives and be happy. Unfortunately, racism is rooted very deeply in our societies and we can no longer overlook it, accept it, and find excuses for it.

Article originally published ilhamwrites.wordpress.com

Ilham Essalih

Ilham Essalih is a Belgian-Arab book reviewer and Ph.D. student in Postcolonial Literature. Her research focuses on the gendered dimensions of postcolonial trauma in the literature of Africa and the Arab world. IG: @ilhamreads Twitter: @ilhamreads